About this text

This revision of the book was last updated on December 8, 2025.

|

This is an old revision of the Remix. The current revision can be viewed here. |

CAUTION - CHAPTER UNDER CONSTRUCTION!

NOTICE: If you are NOT enrolled in the CSC 230 course that I teach at SFSU, you probably are looking for the “public version” of the book, which I only update between semesters. The version you are looking at now is the “CSC230 version” of the book, which I will be updating throughout the semester.

This chapter was last updated on June 19, 2025.

This work, "Discrete Math - The MKD Remix" by Mark Kelly Davis, is adapted from “Discrete Math” by Mohamed Jamaloodeen, Kathy Pinzon, Daniel Pragel, Joshua Roberts, and Sebastien Siva. “Discrete Math” is used under CC BY-NC 4.0. All files for “Discrete Math” are available at its associated GitHub repository.

This work, "Discrete Math - The MKD Remix", is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 by Mark Kelly Davis.

|

If you were a student in my course during the Spring 2024 semester, the version of the book you used can be found here. If you were a student in one of my courses during the Fall 2024 semester, the version of the book you used can be found here. If you were a student in one of my courses during the Spring 2025 semester, the version of the book you used can be found here. If you were a student in one of my courses during the Fall 2025 semester, the version of the book you used can be found here. |

How does the Remix differ from the original work?

The remixer’s goal is to adapt the original “Discrete Math” to create an OER textbook for a one-semester Discrete Mathematics/Discrete Structures course for Computer Science students who have some experience coding in Java, Python, or another high-level programming language, and have completed an Algebra Ⅱ-level (or equivalent) mathematics course. The Remix is a work-in-progress that will continue to evolve over time toward this goal.

Use of materials from the Discrete Mathematics Project

The Remix is designed to work with the activity-based lesson materials developed by the Discrete Mathematics Project (DMP.) See the Appendix: For Instructors for information on how the remixer uses these lessons with the text.

Alignment To Standards

The remixer’s intent is that the Remix:

-

address topics and learning outcomes listed for

-

ACM/IEEE-CS/AAAI Joint Task Force on Computer Science Curricula "Computer Science Curricula 2023" MSF-Discrete: Discrete Mathematics

-

ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Task Force on Computing Curricula "Computer Science Curricula 2013" Discrete Structures (DS) but omitting the DS/Discrete Probability topics and learning outcomes.

Note: ACM CCECC "Computer Science Curricular Guidance for Associate-Degree Transfer Programs with Infused Cybersecurity" Discrete Structures Knowledge Area (DS) is a list of learning outcomes and assessment rubrics that does not specify topics, so the remixer preferred the 2013 document to that June 2017 update. -

California Community Colleges (CCC) C-ID Math 152: Discrete Structures content areas Ⅰ through Ⅴ, omitting area Ⅵ. Discrete Probability.

Note that the content listed for C-ID Math 152: Discrete Structures is identical to the topics listed for ACM/IEEE-CS CS2008 Review Taskforce "Computer Science Curriculum 2008: An Interim Revision of CS 2001" Discrete Structures (DS). -

additional topics from the ACM CCECC Software Engineering curriculum 2005 Discrete Structures Mathematics course.

-

Other Considerations in the Remix

In addition to using activity based lessons and aligning to the standards, the Remix aims to:

-

use terminology, definitions, notation, and symbols that align with commonly-used textbooks such as Kenneth H. Rosen’s Discrete Mathematics and Its Applications, 8th Edition.

-

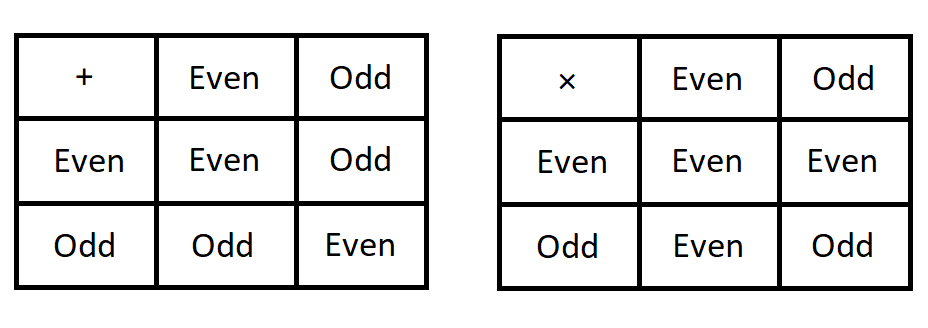

give students the opportunity to learn new content based on what they already know then to move toward building a more formal understanding of the content (e.g., pointing out that the set of odd integers and the set of even integers are the two equivalence classes of an equivalence relation, , and that the rules for adding and multiplying "odds" and "evens" is an example of modular arithmetic.)

-

organize the content in "chunks" for ease of reading and digestion of new ideas

-

refer to original sources (e.g., Pascal’s handwritten triangle as well as earlier non-European references to and uses of the number triangle.)

If you are looking for an OER textbook for a Discrete Mathematics course intended primarily for Mathematics majors (e.g., one that does not include topics like analysis of algorithms and binary tree traversal), there are many suitable ones that exist. For example, see Oscar Levin’s Discrete Mathematics: An Open Introduction, 4th edition.

About the use of Python in the Remix

The Remix is intended for a course that does not require programming. Python is not part of the course content.

The original “Discrete Math” uses Python code samples throughout the textbook and includes "Introduction to Python" as its 3rd chapter. The Remix repurposes this content: Code samples in the Remix are used as "pseudocode that can run on a computer," with coding that uses "just enough Python" to illustrate important abstract ideas and concepts. Most of the existing Python examples were altered, and many new Python examples were introduced throughout the Remix. Note that, in order to illustrate concepts and ideas in the style of pseudocode, much of the Python code shown in the Remix avoids using built-in functions and often uses less efficient data structures and algorithms! For example, in the chapter "Algorithms & Big-O", code samples for sorting and searching avoid using built-in Python functions in order to illustrate all steps needed by the algorithm. In many cases, a comment can be found near a non-optimal code example that explains or illustrates a more Pythonic way of coding.

Partial list of changes made (or to be made) to the Remix.

-

Terminology, definitions, notation and symbols were changed throughout the Remix to align with other commonly-used textbooks. For example, the Remix defines the set of natural numbers \(\mathbb{N}\) to include the integer 0 as an element; this definition is very common and is in fact a "standard" that appears in International Standard ISO 80000-2:2019, Quantities and units — Part 2: Mathematics.

-

In the chapter "Introducing Discrete Mathematics," informal definitions of foundational mathematical ideas needed in the course are introduced. This is done so that learners can see what they do (or do not) already know and create the necessary basis to learn the course content. In addition, a new Appendix, "On-Demand Math Resources" was written which includes material that learners can refer to as needed.

-

The original chapter "Introduction to Python" was moved to the appendices.

-

The original chapter "Counting" was split into two chapters, "Counting: Arithmetic Techniques" and "Counting: Permutations And Combinations". The first of these chapters is placed near the beginning of the book, but the second is place much later, after sequences and recurrence relations have been discussed.

-

The order of the chapters "Set Theory" and "Logic" was swapped. New material was inserted into each of the two chapters.

-

A new chapter, "Proofs: Basic Techniques," was written and inserted after "Logic."

-

The chapter "Number Bases" is based on the original chapter "Number Theory," but the content on divisibility, congruence, and modular arithmetic was moved into the remixed chapters "Introducing Discrete Mathematics" and "Relations."

-

The chapter "Sequences and Recursion" is based on the original chapter "Sequences, Recursive Definitions, and Induction," which was split into two new chapters, "Sequences and Recursion" and "Proofs: Mathematical Induction." "Sequences and Recursion" appears before and as a lead-in to "Functions" since sequences are a special case of functions and recursion is often used to define functions.

-

The chapter "Functions" was moved to its new position, several chapters after "Set Theory." This was done for the following reasons:

-

The learner is expected to have a basic working understanding, from previous classes, of the one-to-one correspondence concept: A unique pairing of each element in one set with elements in another set.

-

The learner is expected also to have a basic working understanding of the function concept: A rule/mapping/association that takes certain objects as inputs and assigns each such input to exactly one output object.

-

It is likely that the learner has some ability to work with function notation and operations such as composition and inversion of functions from previous mathematics courses.

-

The remixer felt that a precise, formal definition of function, as well as properties such as injectivity and surjectivity, could be delayed until after learners had used their previous knowledge of functions.

-

-

A new chapter, "Relations," was written to include topics listed in the ACM/IEEE-CS/AAAI and CCC C-ID courses but absent from the original work, and was inserted after "Functions". This chapter also includes some of the content on divisibility, congruence, and modular arithmetic from the "Number Theory" chapter of the original work.

-

The chapter "Proofs: Mathematical Induction" is based in part on the original chapter "Sequences, Recursive Definitions, and Induction," but the content of this chapter was heavily rewritten and new content was inserted. This chapter was placed immediately before the chapters "Rates of Growth of Functions" and "Algorithms and Their Analysis" so that mathematical induction can be viewed as a way of validating algorithms rather than as just another more complicated proof technique.

-

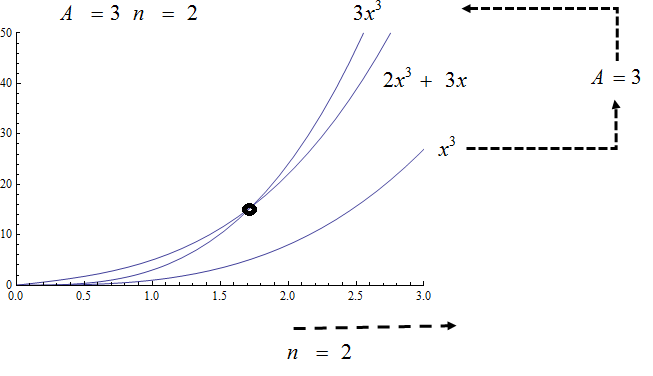

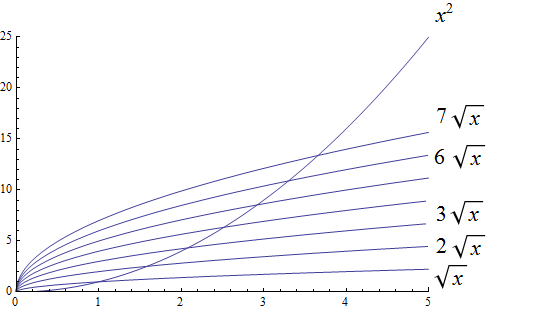

The order of the chapters "Algorithms" and "Growth of Functions" was swapped, then the title "Growth of Functions" was changed to "Rates of Growth of Functions" and the title "Algorithms" was changed to "Algorithms and Their Analysis." New content was inserted into each of the chapters and existing content was revised.

Note that algorithms and their analysis are not mentioned explicitly as topics to be included in the ACM/IEEE-CS/AAAI and CCC C-ID courses, but these topics fit naturally as a motivation to learn much of the other content of the Remix.

-

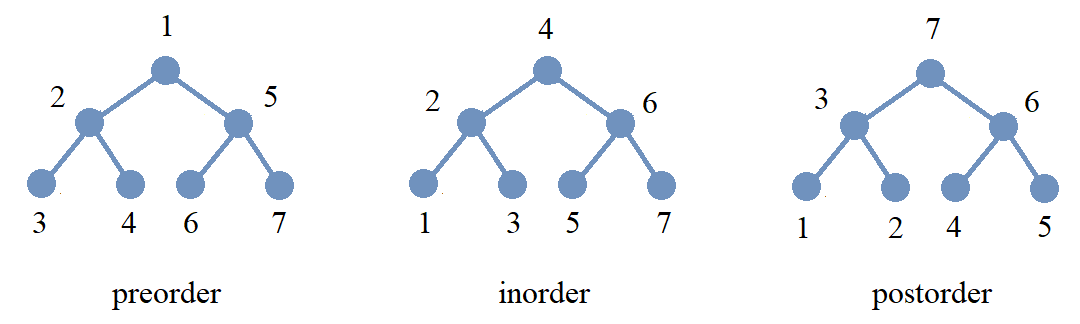

The original chapter "Graph Theory" was split into two chapters, "Graphs" and "Trees". Additional content will be introduced into each of the new chapters.

1. Introducing Discrete Mathematics

NOTICE: If you are NOT enrolled in the CSC 230 course that I teach at SFSU, you probably are looking for the “public version” of the book, which I only update between semesters. The version you are looking at now is the “CSC230 version” of the book, which I will be updating throughout the semester.

This chapter was last updated on July 9, 2025.

Welcome to the Remix! I hope this textbook provides you an opportunity for a stimulating and intellectually enjoyable learning experience.

Mathematics is one of human civilization’s greatest tools: It involves pattern noticing, collecting, comparing, counting, generalizing, formalizing, and abstracting. The development of mathematics is a continuing work that spans at least 5,000 years and many different peoples and cultures. This development will continue long after you and I are gone - never forget that we are living during an era that will be someone else’s Ancient History!

1.1. What is "Discrete Mathematics"?

There seems to be no universally agreed-upon definition of "discrete mathematics," but I will describe to you my understanding of what the phrase "discrete mathematics" means.

Discrete mathematics is the mathematics people use to study and understand structures that are built from individual objects in a way that the individual objects can still be treated as separate from one another within the structure. In such a structure, the individual objects can be put into categories and counted; it makes sense to ask questions like "What is the next object in the structure after this one?" or "Which other objects are the closest to this one?" (where "closest" could refer to physical distance or could mean most similar in color or size) or "How many objects in the structure have a certain property?" Discrete mathematics is a collection of tools that can be used to answer these kind of questions.

As an example, consider a wall, a structure built from individual stones and bricks, part of which is shown in the image.

The

individual

objects in the structure are

the stones and bricks. You can still identify individual objects even though they were combined to build the larger structure, and can classify

an

individual object

by type (either stone or brick) or by color or by the how close to the top of the wall the object

is. You can try to count the total number of individual objects, and you can count the number of individual objects that are next to any one object you choose. The wall is a (non-mathematical) example of a discrete structure.

Image credit: "Vintage Stone And Brick Wall" by Paul Brennan. The image is dedicated to the public domain under CC0.

Here are two more examples of discrete structures.

-

A family of humans can be treated as a discrete structure.

The humans in a family are seen as individuals who can be distinguished from one another. Questions like "Which humans are siblings of this human?" and "Which humans are parents of this human?" and "How many children does this human have?" make sense. -

The set of integers, in the usual order, as represented on a number line is a discrete structure.

It makes sense to ask questions like "What is the next integer after -2?" or "What are the integers that are closest to -2?" for this structure.

Notice that in these examples, the individual objects are of a different nature than the entire structure: Individual bricks and stones aren’t considered a wall, individual humans aren’t considered a family, and individual integers are not a collection of integers.

So what kind of structure is not discrete?

Consider the water in the glass shown in the image. The water in the glass is a structure, but for most of human history it has not been seen as made up of objects that are of a different nature than the structure. That is, many generations of humans have recognized the difference between a wall and the individual stones and bricks that make up the wall, but likely have perceived water as being made up of… water. This is why humans tend to use measurement of quantities of water, using units such as fluid ounces or milliliters.

In our current era,

we humans understand that the water is built from molecules,

which are of a different nature than the water

"structure,"

but because the molecules are so tiny, numerous, and densely distributed throughout the structure, we humans (except perhaps some scientists and engineers)

still use measurement instead of counting and ignore the individual molecules.

For example, a recipe might call for "8 ounces of water" but never would ask for "7.6 × 1024 molecules of water." Notice that the measurement units used do not correspond in any natural way to individual molecules or groupings of individual molecules (unless, perhaps, you are a scientist or engineer.)

Also, notice that the glass container itself is another structure in which the individual molecules tend to be ignored.

Image credit: "Water Glass" by Peter Griffin. The image is dedicated to the public domain under CC0.

Humans use continuous mathematics like calculus to study a structure that is built from objects that are densely distributed throughout the structure. For such a structure, measurement and approximation is more appropriate than counting.

-

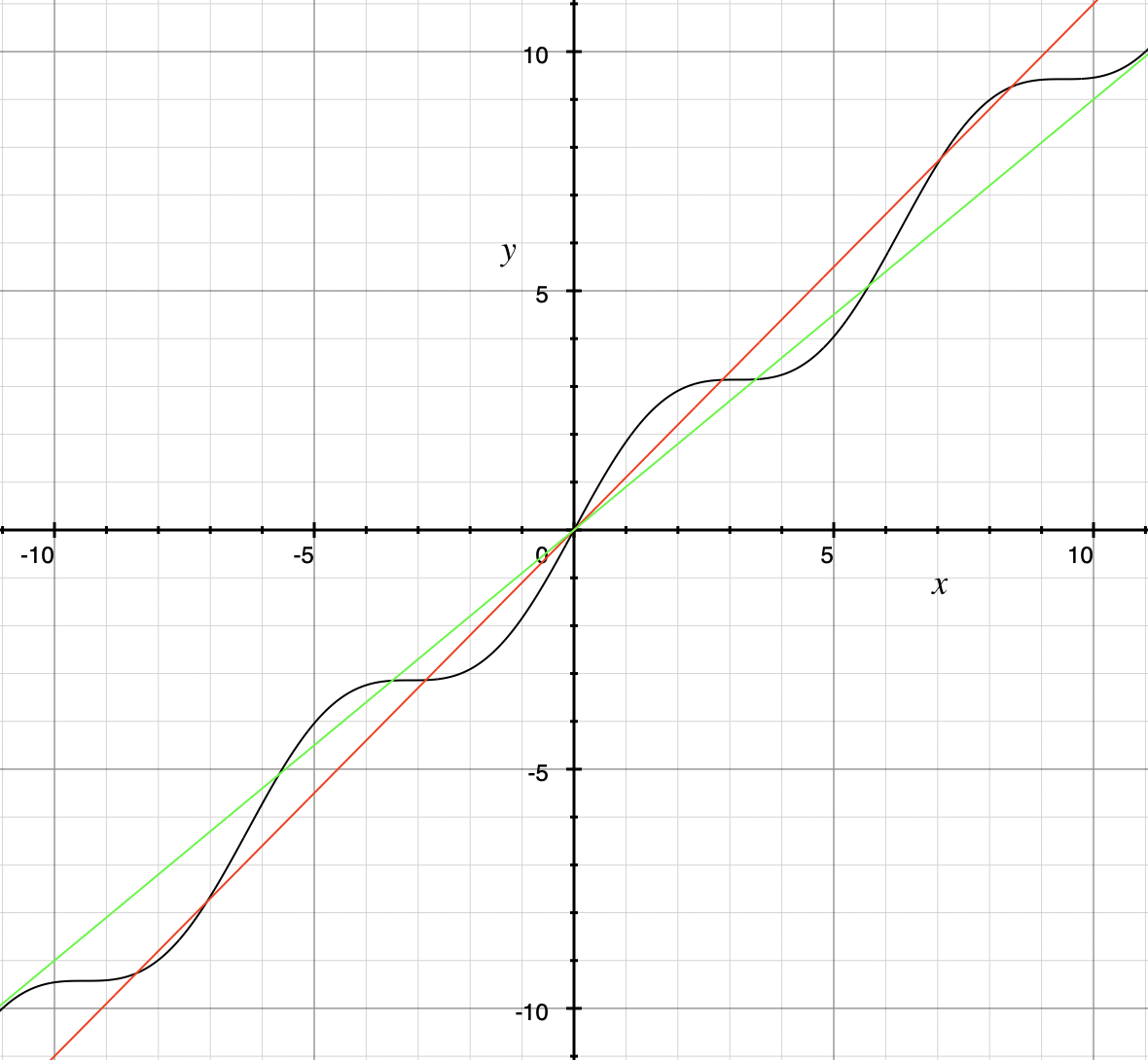

The set of real numbers, in the usual order, as represented on a number line is NOT a discrete structure.

It does NOT makes sense to ask about "the next real number after \(\pi\) on the number line" because if we think c is "the next real number after \(\pi\) on the number line" then we can compute the number \(c_{1} = \frac{c+\pi}{2},\) which is the midpoint of the interval with endpoints \(\pi\) and c, so \(c_{1}\) is closer to \(\pi\) than c is, which means \(c_{1}\) is a better candidate for "the next real number after \(\pi\) on the number line" than c … so the concept "the next real number after \(\pi\) on the number line" does not make sense for this structure as such a number cannot exist! We can just keep computing numbers that get closer and closer to \(\pi\) over and over again. Likewise, "the real numbers that are closest to \(\pi\)" do not exist.

Instead, it makes sense to talk about "the real numbers that differ from \(\pi\) by less than \(\epsilon\)" where \(\epsilon\) is some positive real number (The symbol \(\epsilon\) is the Greek letter "epsilon".) By choosing \(\epsilon\) as small as we like, we can describe the real numbers that are as close to \(\pi\) as needed to use as approximations to \(\pi.\) This is why and how limits are defined and used in courses like precalculus and calculus, subjects that involve the real number line.

Note 1: You could use any other real number instead of \(\pi\) in the discussion above because the argument will still be valid. For example, "the next real number after \(-2\) on the number line" and "the real numbers that are closest to \(-2\) on the number line" do not exist since you can choose numbers that get closer and closer to \(-2\) such as \(-1,\) \(-1.5,\) \(-1.75,\) and so on.

Note 2: The technique used to justify that "the next real number after \(\pi\) on the number line" does not exist is called proof by contradiction and will be discussed along with other techniques in the Proofs: Basic Techniques chapter of this textbook.

Note 3: Is \(\pi\) really on the number line? Click here to view an artist’s explanation about where \(\pi\) lies on the number line. Be warned that some of what this artist says (about history, about \(\pi\) being equal to 3.14) is not correct, but the visualization still may be helpful to you.

Note 4: FYI, the set of real numbers is called the continuum in advanced mathematics courses.

1.2. To The Student: Some Things To Know Before You Begin

Here are some things to orient you.

1.2.1. How To Use This textbook

The Remix is designed to build on your previous knowledge, and then build new knowledge and understanding by visiting the topics over and over again. In the next subsection, the basis of foundational mathematical ideas are discussed. You are encouraged to read through all of those foundational topics and to work through the Questions and Challenges.

There are two analogies that I, the remixer, like to use here:

-

Think of the course presented in the Remix as a language course.

You will use this language to talk about mathematics and computer science as you continue along your professional path. You cannot master a new language by learning some words or grammar in the first few weeks of a language course and then "forgetting" that content later, but still succeed in the course and master the language to use beyond the course. You need to assume that everything you learn in this textbook will apply later in the textbook and in your later learning. One of the goals of this textbook is to help you build a broad and rich vocabulary in discrete mathematics and a way of thinking that will apply to your future work. -

Think of the course presented in the Remix as exercising at a gym.

You will build your strength and awareness about your abilities by working out. It may be tempting to watch others "demonstrate" how to do certain exercises and then choose not to do them yourself, but you are selling yourself short. A physical trainer usually knows already what they are capable of doing, so it is no compliment if you tell them "Wow, you’re really strong"… the trainer’s goal is to get you to say "Wow, I’m starting to get really strong!"

1.2.2. Foundations

Learning discrete mathematics requires putting together old ideas in new ways and adding new ideas to your mix.

This subsection highlights some of the ideas you will need to work with in order to get the most out of this textbook. Also, you’ll find opportunities here to practice with the built-in tools that are part of the textbook. Some of these ideas may be old for you, but others will probably be new. To use this textbook effectively, you’ll need to be able to work with each of these ideas with relative ease. If a few of these ideas are brand new to you, that is fine: All of these ideas will be discussed again, much more formally and in greater detail, later in the textbook.

I encourage you to read all of the topics discussed below. Don’t skip anything, even if it looks "old" because there may be some new ways of understanding the old ideas that are introduced and that will be used later in the course.

-

A set is an unordered collection of zero or more objects. You can think of a set as a list of the names of the objects included, but we do not care about the order of the names in the list and we do not care if the list contains duplicate names.

An example is the set of the names of the additive primary colors of light which can be written as \[\{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"} \}\] which contains exactly three elements: "blue", "green", and "red." It does not matter that "red" appears twice, and it does not matter that the order of the colors in the list "blue", "green", and "red" is different from the order used in the previous set notation. We could define the same set with any other list that contains the same three elements, for example, \(\{ \text{"green"},\,\text{"red"},\,\text{"blue"} \}.\)

As you will see in the Set Theory chapter, it is common practice to use uppercase English letters to stand for sets; this is similar to how lowercase letters are used as variables or constants in algebra. For example, you could write \[P = \{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"} \}\] which allows you to refer to the set as P instead of needing to read the list of elements every time you want to talk about the set. This is like using the Greek letter π instead of needing to read off the first few digits of the non-repeating decimal expansion 3.14159265359… every time you refer to that number.-

NOTE 1: In mathematics, a set like \(P,\) that is, \(\{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"} \}\) is treated as a constant, so you cannot remove elements or insert new elements once a set has been defined and described. As an example, if you wanted to insert the name "white" into the set, you would need to define a new set \[ C = \{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"},\,\text{"white"} \}\] that contains four elements by appending "white" to the list used to define the old set P.

-

NOTE 2:

-

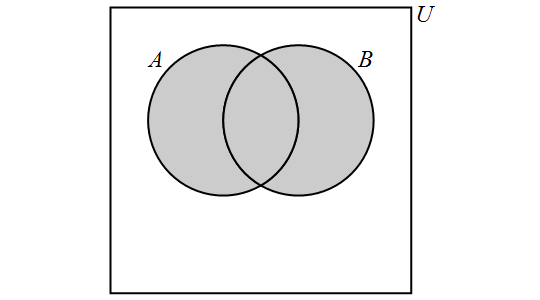

One way of creating a new set from two other sets is to form the union of the two sets. The union of two sets is formed by joining the sets.

For example, If \(P = \{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"} \}\) and \(T = \{ \text{"yellow"},\,\text{"red"},\,\text{"blue"} \}\), then the union of the two sets is \(\{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"}, \, \text{"yellow"},\,\text{"red"},\,\text{"blue"} \},\) the set that contains the colors that are in at least one of the sets \(P\) and \(T.\) -

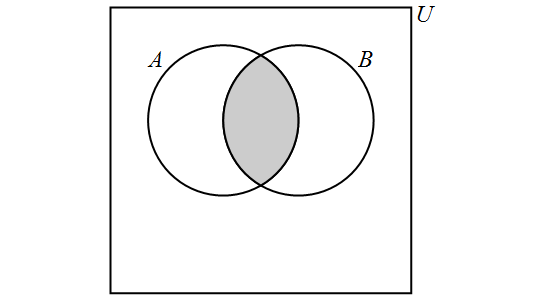

Another way of creating a new set from two other sets is to form the intersection of the two sets. The intersection is the meeting of the two sets.

For example, If \(P = \{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"} \}\) and \(T = \{ \text{"yellow"},\,\text{"red"},\,\text{"blue"} \}\), then the intersection of the two sets is \(\{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"blue"} \},\) the set that contains the colors that are in both of the sets \(P\) and \(T.\)

Likewise, if \(S = \{ \text{"yellow"},\,\text{"cyan"},\,\text{"magenta"} \},\) the set of additive secondary colors, then the intersection of \(P\) and \(S\) is the set \(\{ \},\) the set that contains zero elements. We call the set \(\{ \}\) the empty set.

-

-

NOTE 3: We can define a subset of any set by selecting zero or more of the members of the set. For example, \(\{ \text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"} \}\) and \(\{ \text{"green"} \}\) are subsets of \(\{ \text{"red"},\,\text{"green"},\,\text{"blue"},\,\text{"red"} \},\) and so is \(\{ \},\) the empty set.

-

NOTE 4: A set can also be defined by a property instead of a list. This will be explained in the Set Theory chapter.

-

-

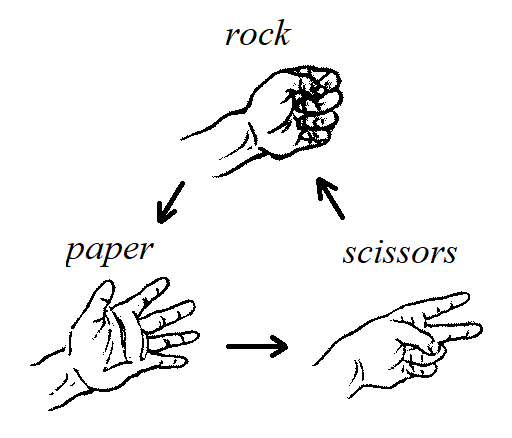

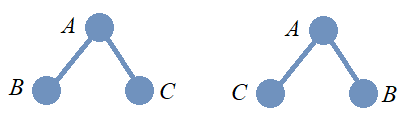

A one-to-one correspondence between two sets A and B is a pairing of each member of the set A with exactly one member of set B, and each member of set B with exactly one member of set A.

-

A natural number is one of the nonnegative integers. The letter \(\mathbb{N}\) denotes the set of natural numbers, that is, \[\mathbb{N} = \{ 0,\,1,\,2,\,3,\,\ldots \}\] where the three dots are used because we cannot write down the entire list of natural numbers.

-

NOTE: We almost always use the base-ten (decimal) place-value system to represent natural numbers, but later in this textbook you will see that there are other number base systems such as the base-two (binary) place-value system, that are useful in some contexts.

-

WARNING: The definition of natural numbers used in this textbook is an ISO standard, but be aware that other textbooks and sources may use the "nonstandard" definition that the natural numbers are the positive integers. In this textbook, the set of natural numbers ALWAYS include zero as well as the positive integers, which is the standard definition.

-

-

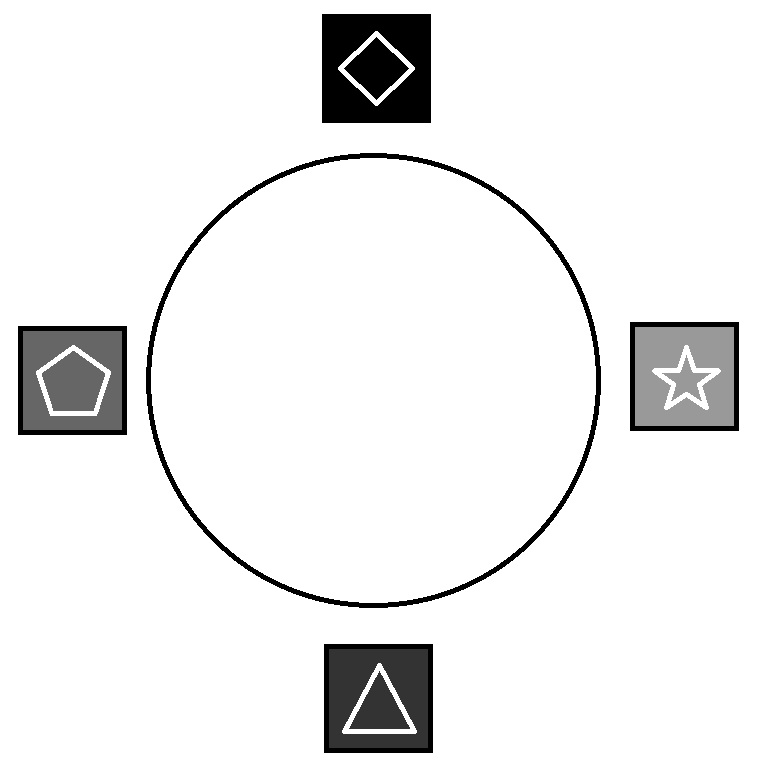

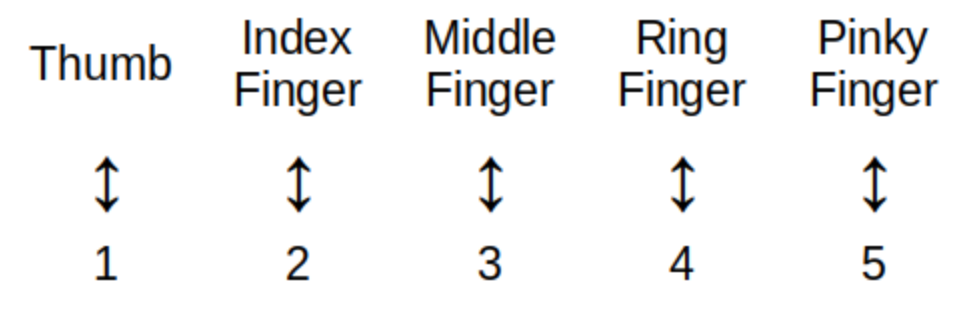

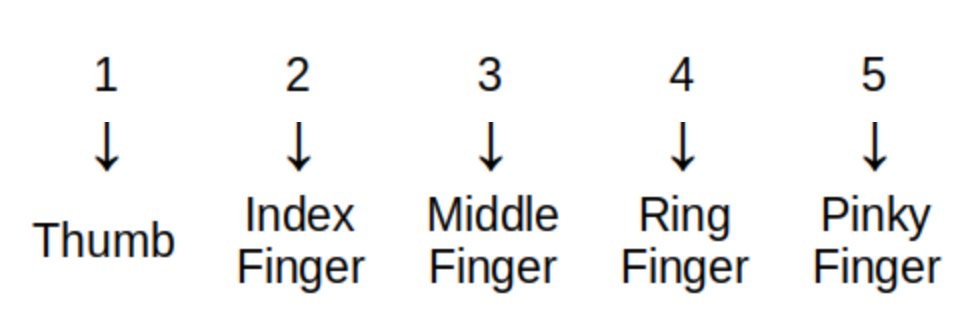

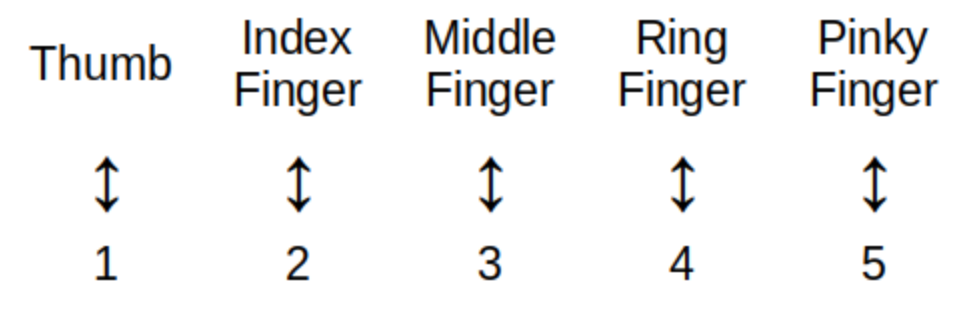

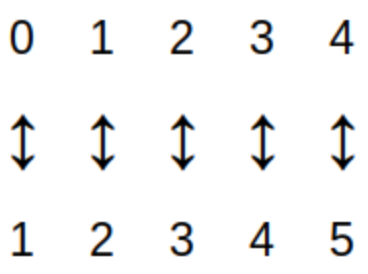

A set is called a finite set if either the set is empty or there is a one-to-one correspondence between the set and \(\{1, 2, \ldots , n \}\) for some positive integer \(n.\) For example, the image represents how a child may "count up to 5" by pairing fingers with the numbers in \(\{1, 2, \ldots , 5 \}.\)

A set that is not a finite set is called an infinite set. Both finite and infinite sets will be discussed in more detail in the Set Theory chapter.

-

You may be surprised to see Counting listed as a topic in a university-level course because you probably learned to count by putting physical objects (like fingers) into a one-to-one correspondence with number words such as "one, two, three, four, five" when you were a young child. That way of counting one by one is fine for small sets, but the counting techniques discussed in this textbook let you count the number of elements in very large finite sets quickly.

-

The Pigeonhole Principle states that if \(n\) is a positive integer and \(n+1\) objects are going to be assigned to \(n\) categories then one of the categories must be assigned at least 2 of the objects. Click here to see a commonly-used photoshopped image that illustrates this principle.

-

A function from set D to set C is a rule that assigns to each element in D (that is, to each input value) exactly one output value from C. We also say each input value is mapped to the output value. A much more formal definition will be given in the Functions chapter of the textbook, but for now it is enough to understand functions in this way.

-

The rule may be represented by a mathematical equation, a verbal description, a table of paired values, a plot of points, … or even code 😎!

-

The set D of all input values is called the domain of the function.

-

The set C that contains the output values is called the codomain of the function.

-

The range of the function is the set that contains only the output values and no other elements. The range is always a subset of the codomain C, but may not contain every element of C. That is, some elements of C may not be outputs for the function. It is often important to distinguish the range from the codomain; this is discussed in detail in the Functions chapter.

-

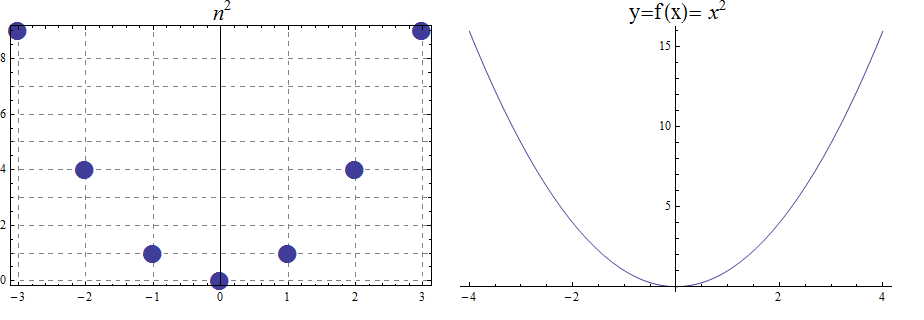

Here is another example.

-

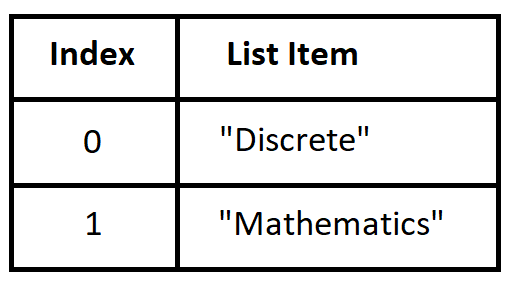

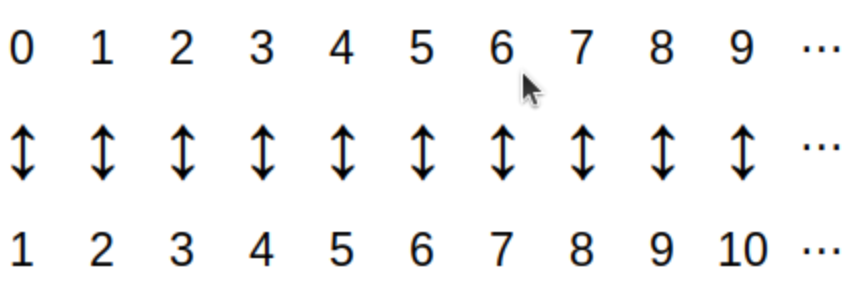

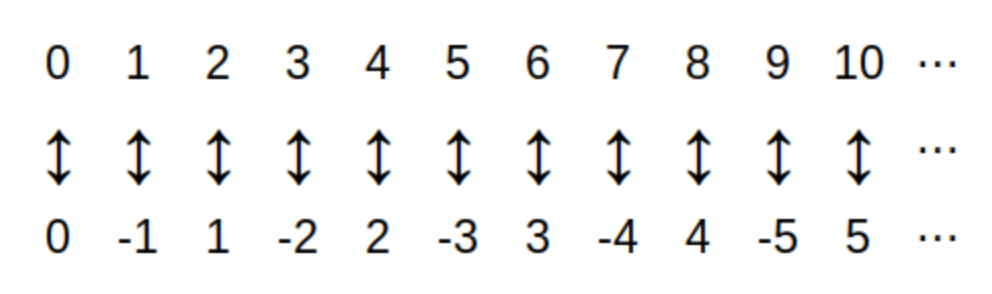

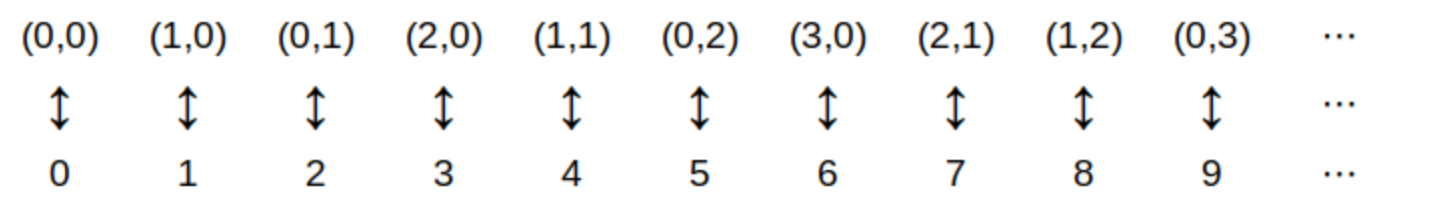

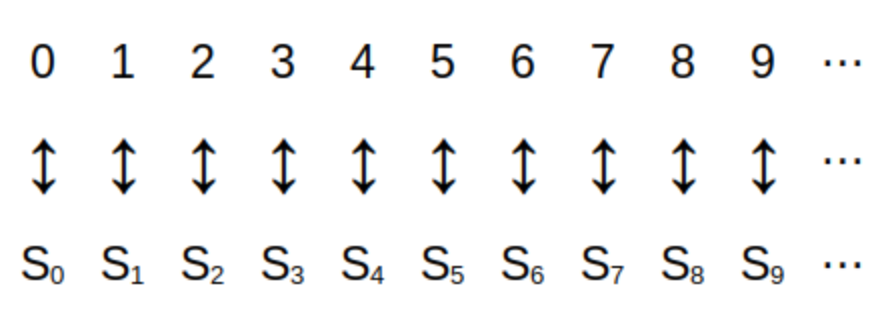

A sequence is a function from the natural numbers, or a subset of the natural numbers, into another set (e.g., the natural numbers, or the real numbers, or a nonnumerical set.) For example, we can define a sequence by the rule \[a_{i} = 2i+1 \text{ for every natural number } i \] which describes the sequence of positive odd integers \(a_{0} = 1,\) \(a_{1} = 3,\) \(a_{2} = 5,\) and so on.

-

NOTE 1: It is common to use i as a variable in sequence notation because i is the initial letter of the word index. This i has nothing to do with the complex number \(\sqrt{-1}.\) Mathematicians recycle and reuse letters!

-

NOTE 2: It is traditional to write the input variable for a sequence as a subscript instead of putting it between parentheses. In the preceding example, \(a_{i} = 2i+1\) has the same meaning as \(a(i) = 2i+1\).

-

NOTE 3: The output values of a sequence are called terms. For example, the 0th term of the sequence is \(a_{0} = 1,\) the 1st term of the sequence is \(a_{1} = 3,\) and so on.

-

-

A finite sequence is a sequence that is defined for only a finite subset of \(\mathbb{N}.\) That is, the set of input \(i\) values that make sense for the sequence is a finite set.

For example, a child counting up to five on the fingers of one hand is defining the sequence called \(\textit{fingers}_{i}\) that is represented by the image.

Technically, the sequence \(\textit{fingers}_{i}\) shown in the image is the inverse of the child’s actual counting sequence. Because the child assigns to each finger "input" exactly one number "output," the arrows would point up from a finger to the corresponding number.

The sequence \(\textit{fingers}_{i}\) can be written, formally, as \begin{equation} \begin{aligned} \textit{fingers}_{1} {} & = \text{"Thumb"} \\ \textit{fingers}_{2} {} & = \text{"Index Finger"} \\ \textit{fingers}_{3} {} & = \text{"Middle Finger"} \\ \textit{fingers}_{4} {} & = \text{"Ring Finger"} \\ \textit{fingers}_{5} {} & = \text{"Pinky Finger"} \\ \end{aligned} \end{equation} but it is much more common to list the terms of the sequence in order: "Thumb," "Index Finger," "Middle Finger," "Ring Finger," "Pinky Finger."

Notice that Java arrays and Python lists are implementations of the mathematical concept of a finite sequence where the domain is the set of \(i\) values \(\{0, 1, \ldots , n \}\) for some natural number \(n.\)

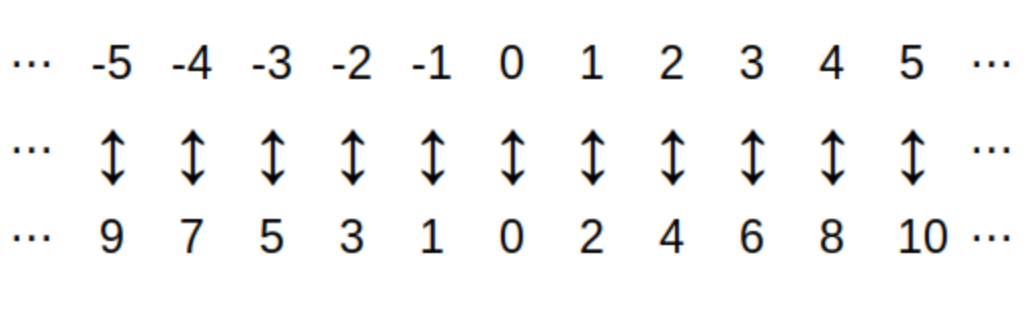

An infinite sequence is a sequence that is not a finite sequence, that is, the there are infinitely many \(i\) values that make sense as inputs for the sequence. For example the sequence \[ \text{isOdd}_{i} = \begin{cases} \text{1} & \text{ if } i \text{ is odd} \\ \text{0} & \text{ if } i \text{ is even} \\ \end{cases} \] is an infinite sequence with domain the integers that has only two output values.

-

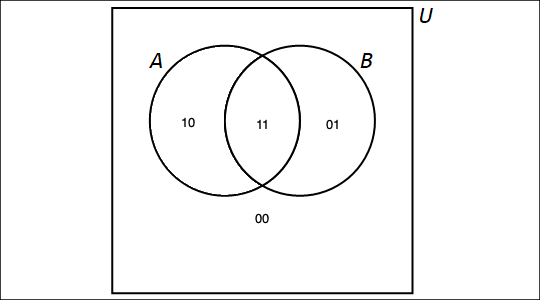

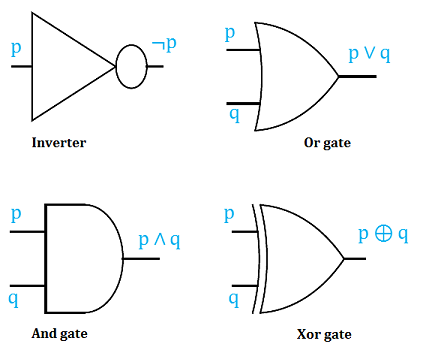

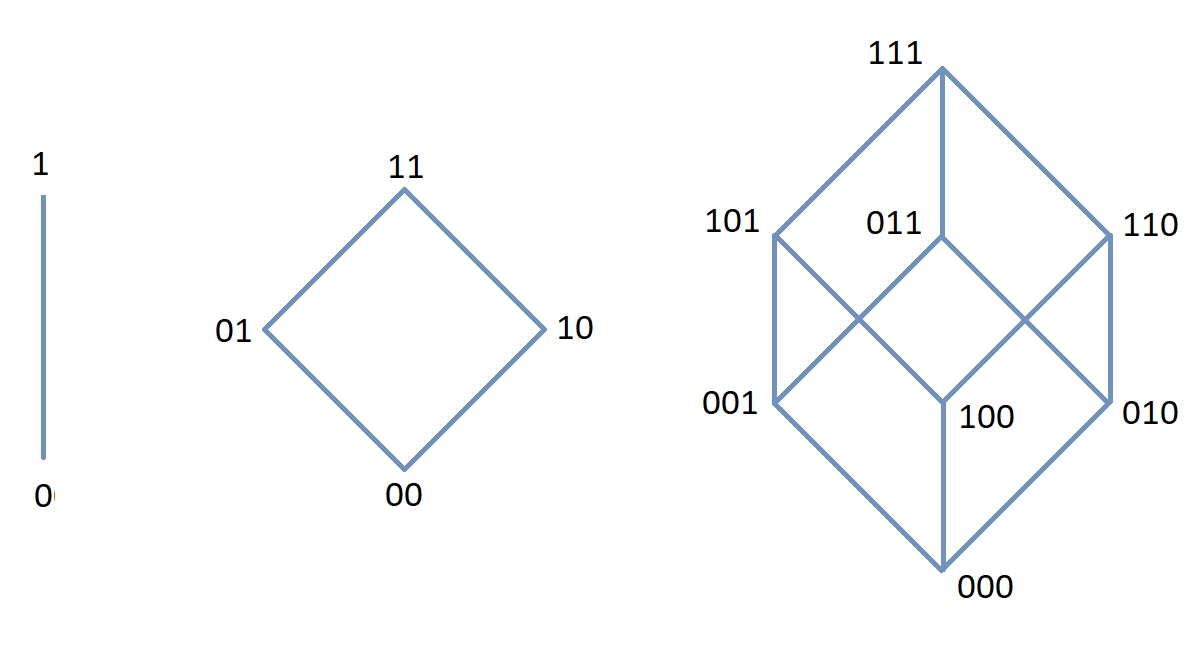

A bitstring is a finite sequence of the bits 0 and 1. Bitstrings are written as a string of 0s and 1s without spaces or commas between the terms of the sequence; for example, 01101011 is a bitstring of length 8. Bitstrings can be used to represent a sequence of answers to "Yes-No" or "True-False" questions, with "1" representing "Yes" or "True" and "0" representing "No" or "False." Bitstrings can also be used to represent numbers in binary notation, which will be discussed in the Number Bases chapter.

-

Summation notation is a "shortcut" used to abbreviate a sum of a finite sequence of numbers, called addends, when the sequence contains a large number of addends.

As an example, the sum \(1+3+5+7+9+11+13+15+17+19\) is abbreviated as \(\sum\limits_{i=0}^{9}(2i+1)\).

As another example, the sum of the first \(500\) positive odd integers, \(1+3+5+\ldots+995+997+999\), is abbreviated as \(\sum\limits_{i=0}^{499}(2i+1)\).-

NOTE 1: The variable i used in summation notation is called the index of summation and the symbol \(\sum\) is the capital Greek letter "sigma." To compute the value of the sum, you generate the sequence of addends by substituting each integer value, starting with the lower limit written below the sigma and stopping at the upper limit written above the sigma, for i into the algebraic expression or function written to the right of sigma, then find the sum of all the numbers in the sequence.

-

NOTE 2: "Infinite sums," more properly called infinite series, are not discussed in the Remix. The sum of an infinite series is defined as the limit of its sequence of partial (finite) sums, and "limits" is a topic from continuous mathematics, not discrete mathematics.

Another use of infinite sum notation is to represent the generating function of a sequence, which is discussed in some discrete mathematics textbooks but not in the Remix. If you want to learn about generating functions, you can read about them in Oscar Levin’s Discrete Mathematics: An Open Introduction, 4th edition.

-

-

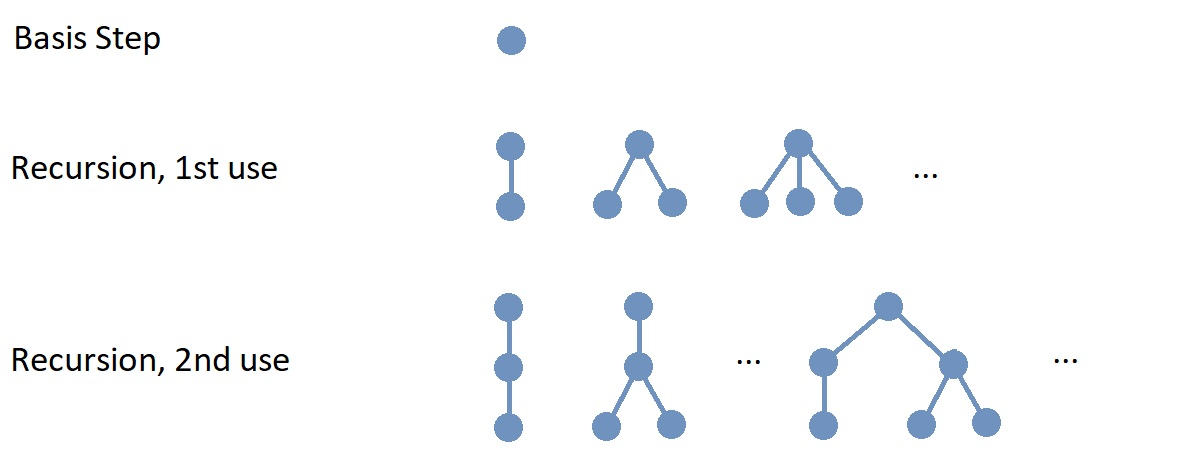

Recursion is a process that defines an object, or computes a value, or describes the construction of an object or set of objects, using steps that refer to one or more previously completed steps.

-

Recurrence relations consist of one or more equations that define a sequence or a function with domain \(\mathbb{N}.\)

-

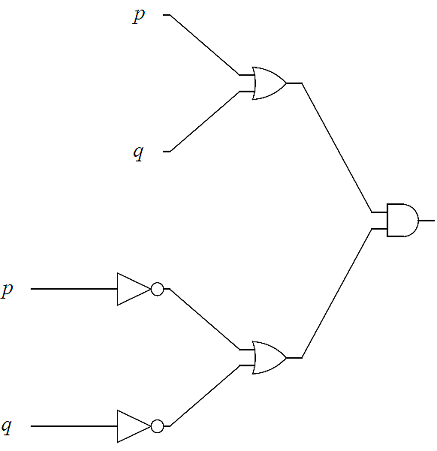

In English, there are four types of sentences, depending on what is being communicated: statements (or declarative sentences), commands, exclamations, and questions. A proposition is a statement that declares a fact that is either True or False (but not both!) In mathematics, we are usually most interested in analyzing and verifying propositions.

-

A predicate is an incomplete proposition that contains one or more variables that need to be filled in to complete the proposition. One example of a predicate is "My major is \(\rule{12mm}{.5pt}\)." Notice that this becomes a proposition once the blank, which represents the variable in this case, has been filled in.

Another example of a predicate is "The positive integers m and n are prime numbers." Again, this becomes a proposition once values are substituted for the two variables.

In this textbook, predicates will often be written in a way similar to functions: + \[ P(m, n) : \text{"The positive integers } m \text{ and } n \text{ are prime numbers."} \] Notice that the output of the predicate is a statement but the output does not tell us whether the statement is True or False - think of this like a programmer: The return value is a string, not a Boolean.

Two predicates are equivalent if for every possible substitution for the variables, the statement produced by the first predicate is true if and only if the statement produced by the second predicate is true.

-

An algorithm is a finite sequence of commands and statements that describe a process for completing a task.

It’s likely that you have learned how to perform many algorithms in your previous mathematics education, but in this textbook (and in computer science in general) it is more important that you learn how to analyze and compare algorithms.

One example is the following (correct but inefficient) algorithm for division of positive integers.-

Task: Given two positive integers a and b, compute the quotient q and remainder r so that

\(a = q \cdot b + r\) and \(0 \leq r < b.\) -

Input: Two positive integers a and b

-

Steps:

-

Set r equal to a and set q equal to 0.

-

If r is greater than or equal to b

-

set r equal to r - b

-

add 1 to q

-

-

If r is greater than or equal to b then repeat step 2

-

-

Output: Integers q and r such that both \(a = q \cdot b + r\) and \(0 \leq r < b.\)

-

q is the quotient, that is, the number of times each of the two assignments under step 2 was executed.

-

r is the remainder, that is, the result of the last execution of step 2, so \(r = a - q \cdot b.\)

-

-

-

Based on the case \(b=2\) in the division algorithm discussed above (and the Challenge), every integer a can be written in the form \(a = q \cdot 2 + r\) where q is an integer and \(0 \leq r < 2.\) The integer a is even if \(r=0\) and is odd if \(r=1.\) So we have a precise formal way of understanding and discussing odd and even integers - this may seem unnecessary (or even completely silly), but as you continue reading this textbook you will see that precise formal definitions and descriptions are useful when you need either to justify that certain statements are true or to validate that certain processes always produce correct and expected results.

-

Suppose that \(a\) and \(b\) are integers, which could be positive or negative or zero. The integer b is called a factor of a (or divisor of a), and a is called a multiple of b if \(a = q \cdot b\) for some integer q. For example, 2 is a factor of 10, and 10 is a multiple of 2, because \(10 = 5 \cdot 2.\) As another example, \(-2\) is a factor of 10, and 10 is a multiple of \(-2\) because \(10 = (-5) \cdot (-2).\)

-

A positive integer n that is greater than 1 is called prime if the only positive integer factors of n are 1 and n itself, and is called composite otherwise. For example, 2 is prime since its set of positive integer factors is \(\{ 1,\,2 \}\), but 6 is composite since its set of positive integer factors is \(\{ 1,\,2,\,3,\,6 \}\).

-

NOTE: The integer 1 is considered neither prime nor composite. The reason for this is beyond the scope of this textbook but would be discussed in a more advanced math course in ring theory.

-

-

Two integers a and b are called relatively prime if the only common positive integer factor of a and b is 1; this is equaivalent to stating that the two integers do not share any prime factors. For example, 10 and 21 are relatively prime integers.

-

A relation on the sets A and B is an association between elements from set A and set B; A and B are often the same set. Relations will be defined much more formally and precisely in the Relations chapter of the textbook.

Here are some examples of relations:-

The ordering relation "is less than," \(x < y,\) for real numbers x and y. So \(3 < 4\) but \(5 \nless 4.\) The slash through the "<" symbol means that "5 is not related to 4" in the way we want.

The orderings \(>\), \(\geq\), and \(\leq\) are also examples of relations. -

The equality relation \(s=t\) for any elements s and t of the same set A.

A related example is inequality, \(s \neq t.\) -

The divisibility relation "a is a divisor of b" (or "a divides b") for integers a and b; this is sometimes written as \(a \mid b.\) So for example, \(2 \mid 4\) but \(3 \nmid 4.\)

-

For two integers a and b, we say that "a has the same parity as b" if either both a and b are odd or both a and b are even.

-

Any function \(f\) with domain A and codomain B is a relation since the function associates each element a in A with exactly one element b of B, namely \(b = f(a)\).

-

A relation can also involve more than two sets. As an example, imagine a database of records that has three fields: a student’s name, a student’s college identification number, and the student’s major. The database can be viewed as a set R of ordered triples. So, for example, if a student named Chris Garcia has identification number 900123001 and is a Computer Science major, the set R would contain as an element the ordered triple ("Chris Garcia", 900123001, "Computer Science").

-

-

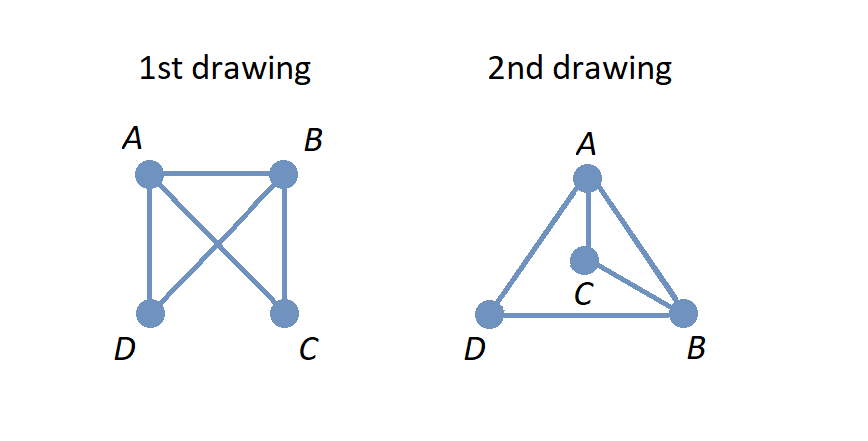

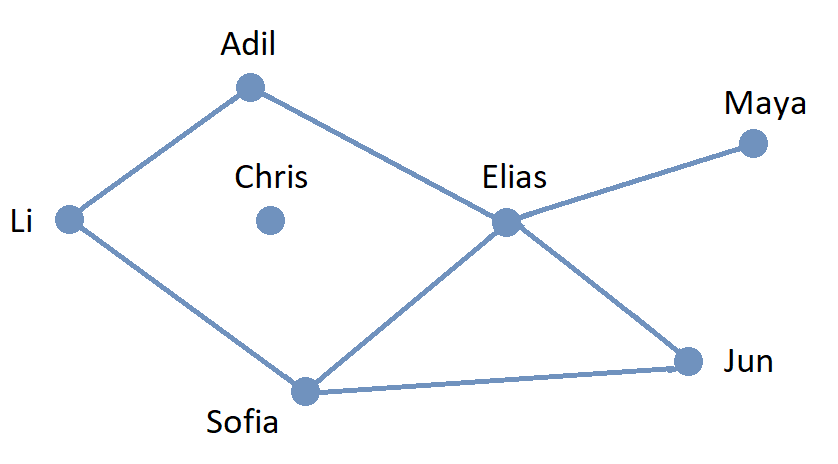

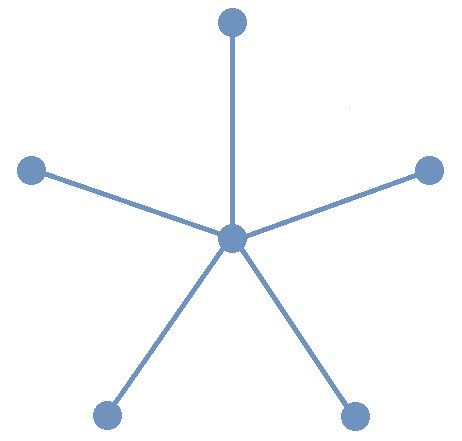

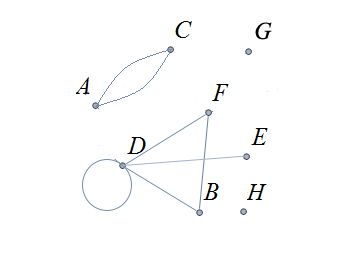

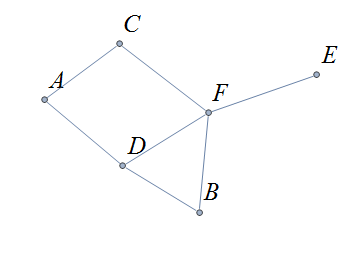

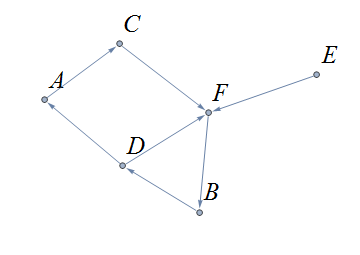

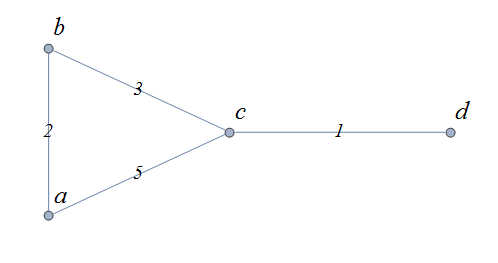

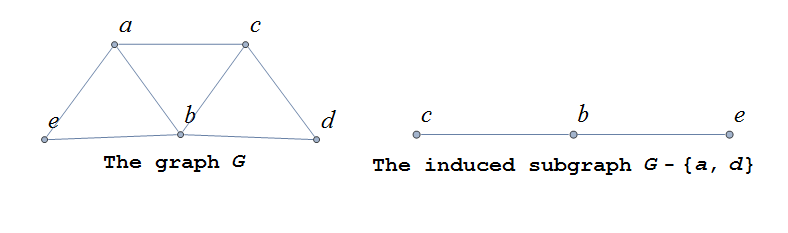

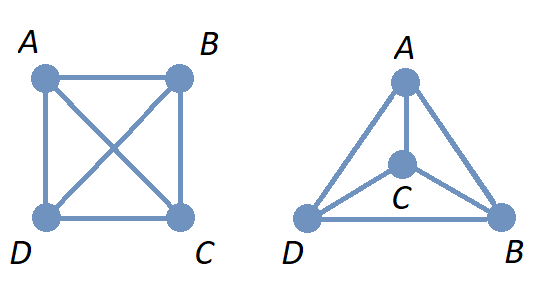

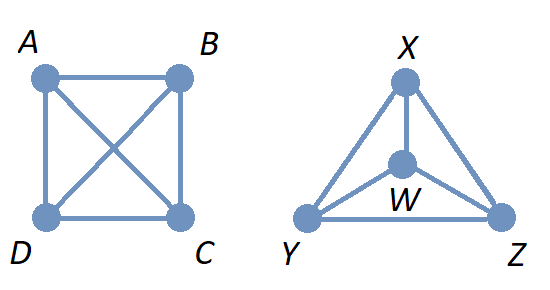

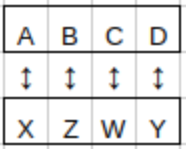

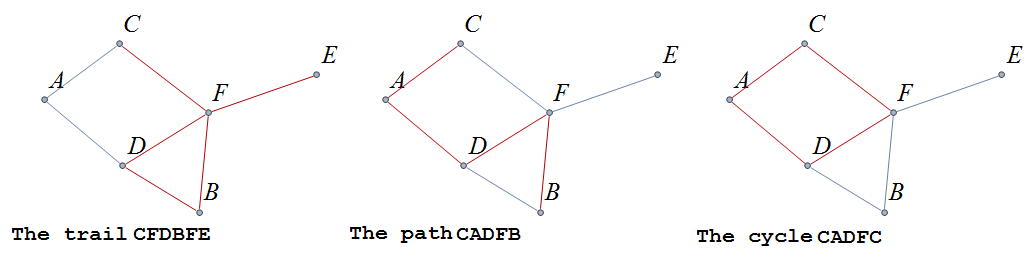

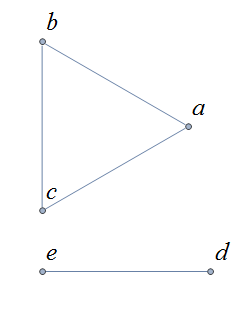

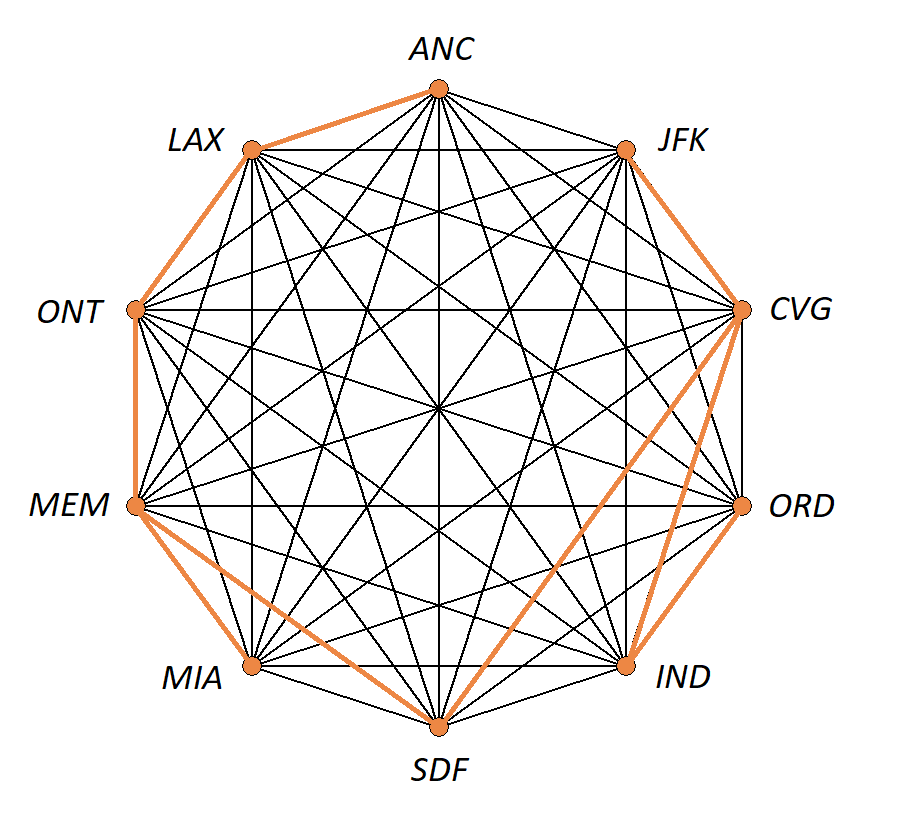

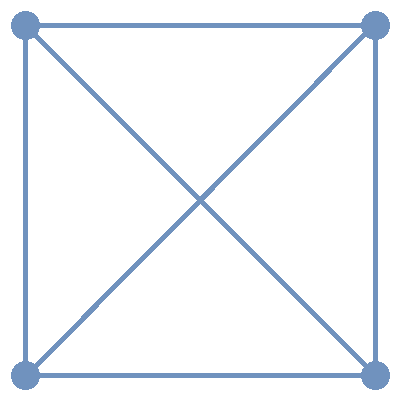

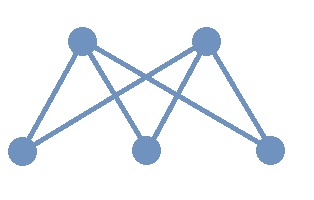

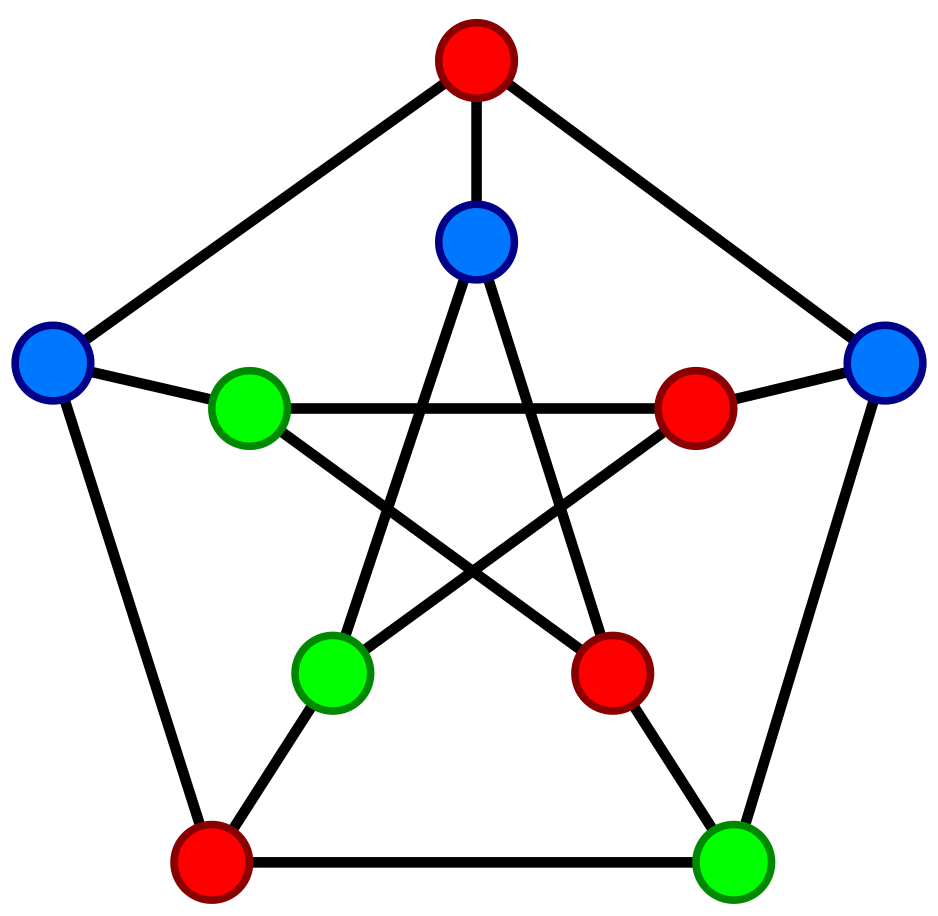

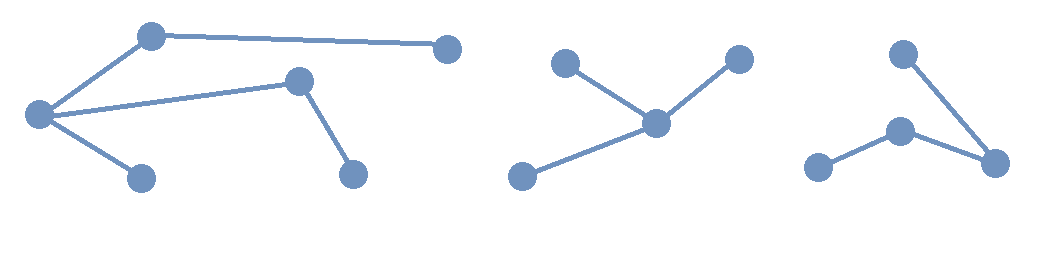

A graph is a mathematical object that consists of vertices (also called nodes) that are connected by edges. Graphs are often represented by drawings like the ones shown in the following examples, but you can also represent a graph in other ways that are easier and more efficient to use in code; this will be discussed in the Graphschapter.

The drawing of a graph is not treated like a geometric polygon: The only two points "on an edge" are the edge’s endpoints. Edges are just connectors between vertices and points that are not indicated as endpoints of an edge are ignored. Also, in a drawing of a graph, the lengths of edges and the straightness or curvedness of edges are not important, just the connections between the edges' endpoints.

| Some high school-level textbooks use the term vertex-edge graph to distinguish this type of graph from graphs (that is, plots of points in the \(xy\)-plane) for equations, functions, or statistical data. |

The design of this book is to introduce each concept informally, as was done for the preceding foundational ideas, then notice properties and patterns, generalize from what has been noticed, and formalize the ideas to prepare for even deeper analysis.

And congratulations if you read through all of those foundational mathematical ideas in this subsection and worked through all the Questions and Challenges! If you compare the list of ideas to the Table of Contents, you will see that you have touched on every one of the topics that will be discussed in this textbook!

1.2.3. On-Demand Math Resources and Library Of Functions Appendices

Two appendices to this textbook contain additional mathematics that you may need to review as you work your way through the textbook.

1.2.4. Do I Need To Know How To Program In Python?

You are NOT expected to know the Python programming language before you start this course.

As you’ve seen above, this textbook contains Python code snippets that are designed to aid your understanding of the mathematical concepts. It is NOT one of the goals of this textbook to teach you Python, but instead "just enough Python" to be able to examine, run, and alter the existing code snippets.

The appendices "An Introduction to Python" and "Python Syntax Examples" cover most of the basic concepts you will need from the Python programming language.

1.3. Applications of Discrete Mathematics

Remixer’s Note: This section is taken from the original “Discrete Math” book, with only a few minor edits.

Discrete mathematics is applied in many areas including the physical, engineering, and increasingly, the social sciences.

1.3.1. Applications to Applied Mathematics

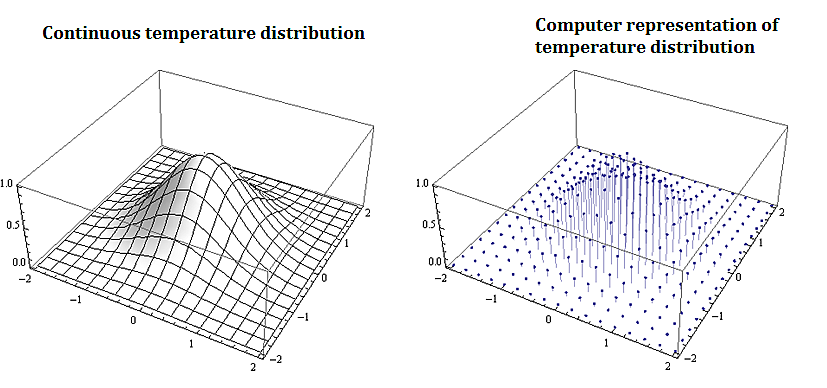

Most problems that involve computational methods, need to be solved using computers. Rather than solve for the temperature map of an entire planar region, we solve for the temperature using a discrete set of mesh or grid of points on a representative subset of the planar region.

1.3.2. Applications to Information Technology and Computer Science

Discrete mathematics is needed for computer science as information and data is stored digitally. Digitally represented data is inherently discrete and is processed using discrete methods. For example a course grid discrete representation of the 2-d temperature distribution from the plate above could be:

\( \left(\begin{matrix}1&1&1\\2&4&8\\3&9&27\\4&16&64\\5&25&125\\\end{matrix}\right) \)

A voter registry may have voters in a database accessible from a list:

\( \left(\begin{matrix}John\ Smith\\Raheem\ Johnson\\.\\.\\.\\Sarah\ Muller\\\end{matrix}\right) \)

Which may need to be accessed and sorted, say geographically or alphabetically.

1.3.3. Applications to Data Science

Data science solutions to many problems use machine learning algorithms that are inherently discrete in nature. The information that needs processing is discrete, as are the basic problems in data science such as classification or clustering problems. In particular

-

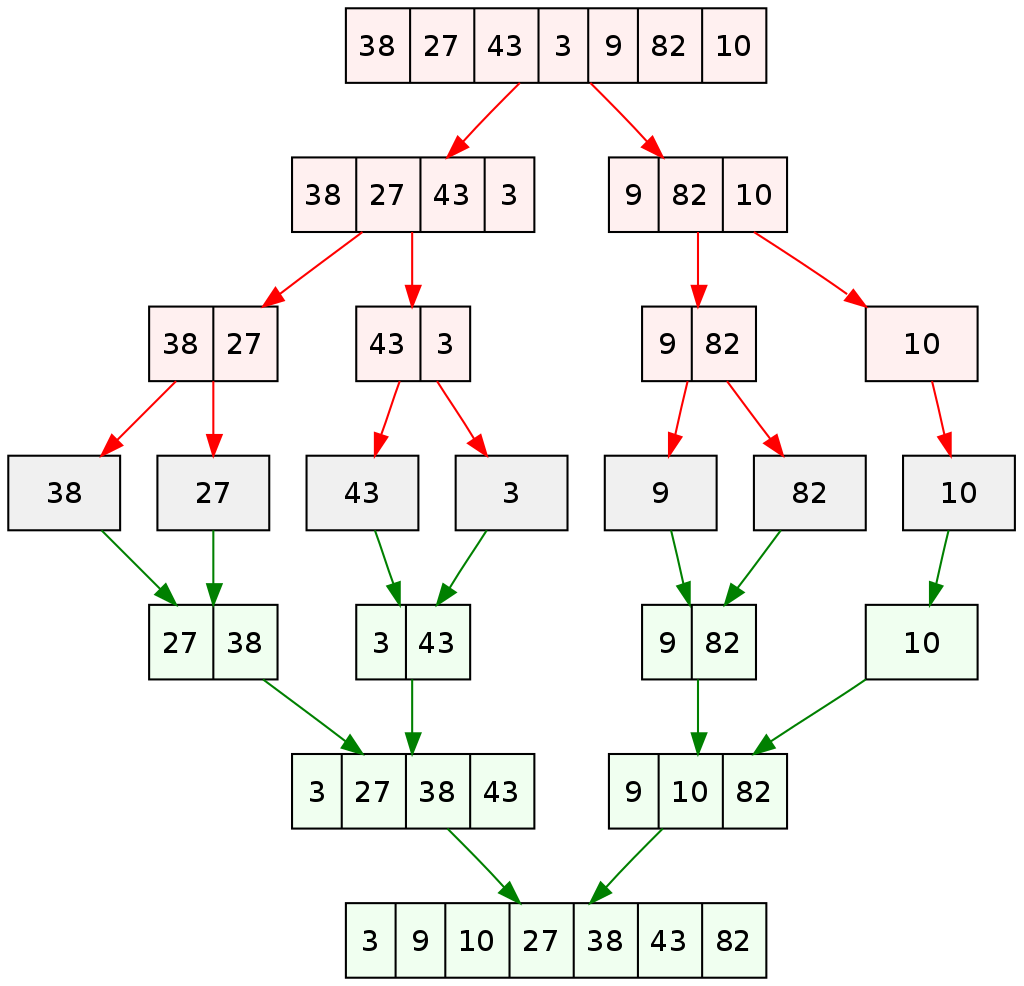

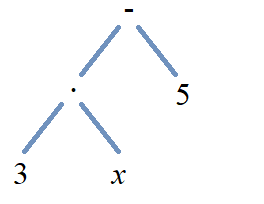

Information consisting of data sets is represented using various data structures including graphical structures such as trees. Data science methods and algorithms involve procedures that manipulate these graphical structures to, for example, networks, classification trees, and decision trees.

-

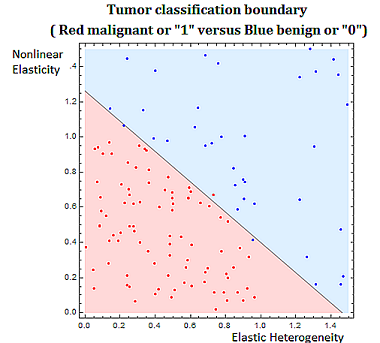

Classification problems are discrete in nature. Classifying tumors as malignant or as benign involves trying to predict if a variable \(Y\) that we can think of as taking on two values either \(0\) or \(1\) either malignant or benign. There are various algorithms used in classification problems, such as the binary tumor classification, including methods from probability.

1.3.4. Applications to Engineering

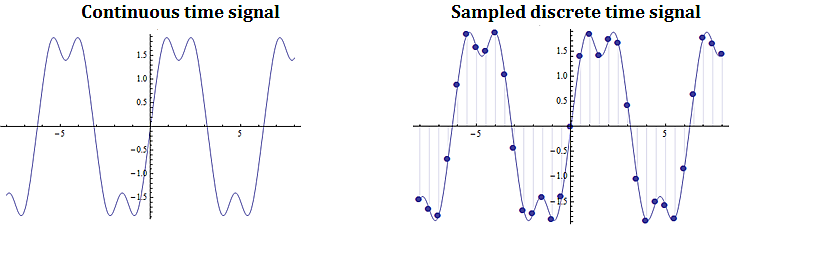

Digital signal processing involves taking a video, audio, or other signal like temperature, pressure, position and velocity, which is continuous, digitizing it and then processing the digital signal mathematically.

1.3.5. Applications of Combinatorics

Combinatorics involves in part the study of counting the number of objects, satisfying a specified condition, from sets of variable size. Enumeration and combinatorics is important in many areas and examples including:

-

Calculating the number of steps an algorithm needs to process a data set of variable size \(𝑛\). This problem is called the computational cost of the algorithm as a function of \(𝑛\).

-

Calculating the possible number of codes in a cryptographic code system

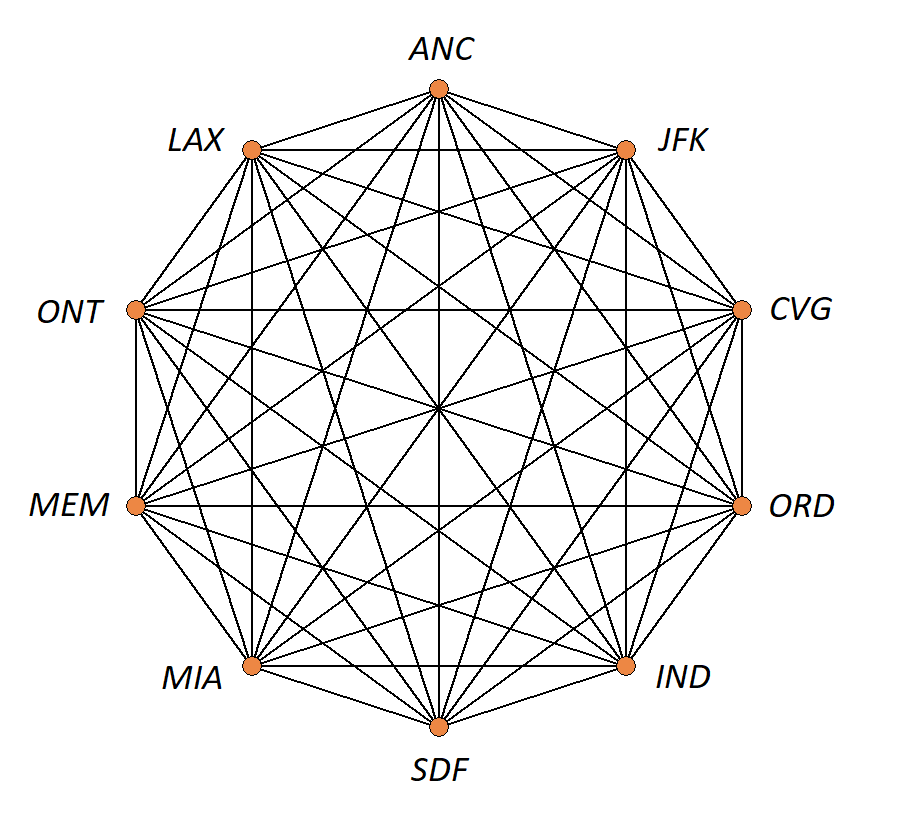

1.3.6. Applications of Graph Theory

Graph theory, which is the study of structures constructed with nodes and the edges joining them, has applications in many fields including,

-

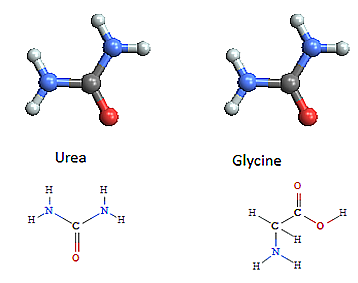

Chemistry - representing molecular bonding and structure

-

Information technology and computer science - ranking pages on the internet, with pages considered as nodes and page links as edges.

-

Industrial engineering and network optimization

-

Traffic routes (computer, internet, air, highway, subway systems) can be represented with stations as nodes and connections as edges.

-

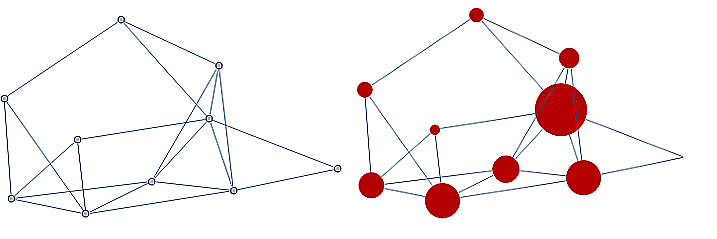

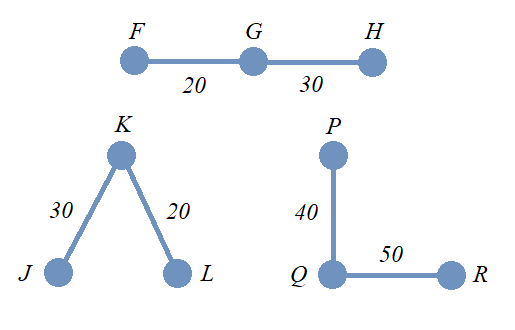

Often we are interested in finding an optimal path in a network such as in the following example, finding the shortest tour over a series of towns on a map.

-

An example of the shortest tour problem, is shown below, using a software solution.

1.3.7. Applications of Probability and Statistics

Many probability assignments are based on counting and combinatorial methods.

-

If we assume that the likelihood of rain is the same on any day in the month of September, we might be interested in the probability that it rains on \(0\) days, it rains on exactly \(1\) day, exactly \(2\) days, etc. Such probability assignments are called discrete distributions, by contrast with continuous distributions like the bell curve.

-

Also probability and statistical techniques are often used in data science. The binary classification problem, of say classifying a tumor as malignant or benign, uses a statistical modeling technique, called regression, specifically logistic regression to determine the strength of the relationship between the independent variable, and dependent heterogeneity variable. In the tumor grading example the independent variable would be \((x_1,x_2 )\) (elastic heterogeneity, nonlinear elasticity), and the dependent variable would be \(Y\), classified as \(0\), or \(1\), (malignant or benign).

1.3.8. Applications to Social Sciences

Discrete mathematical techniques are important in understanding and analyzing social networks including social media networks.

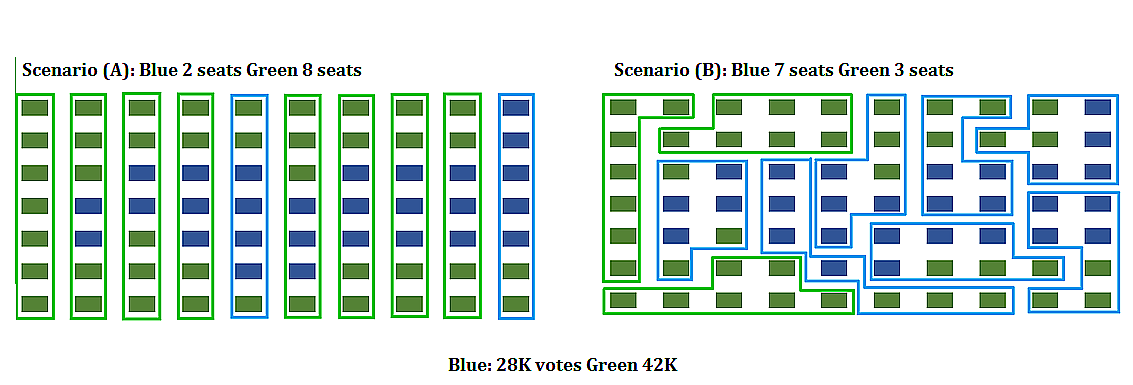

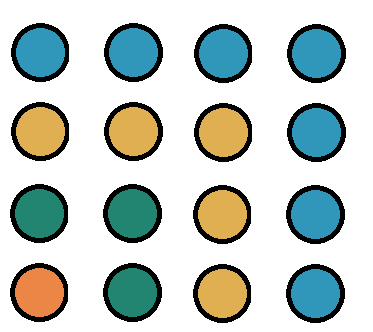

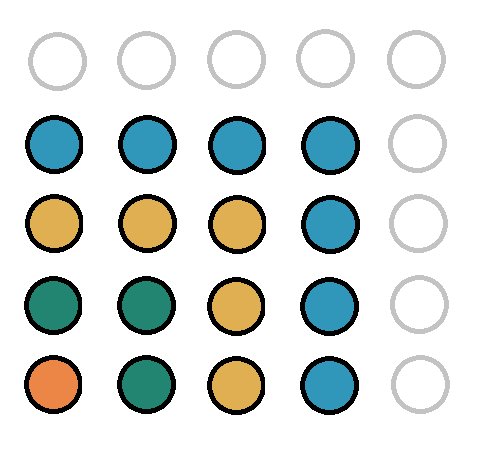

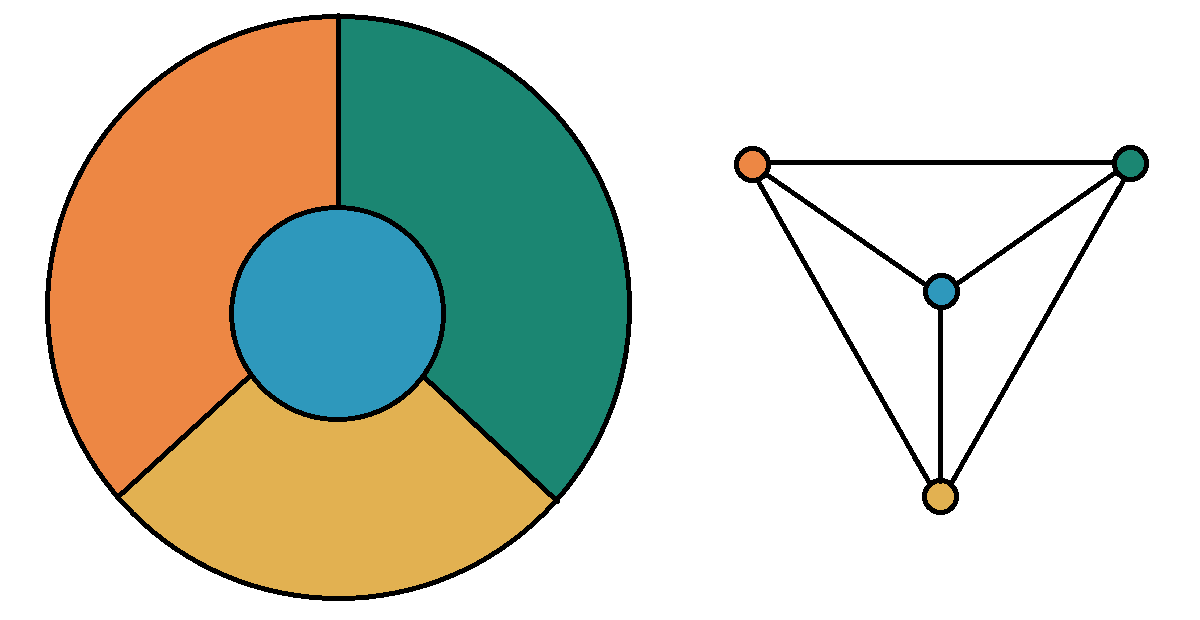

The mathematics of voting is a thriving area of study, including mathematically analyzing the gerrymandering of congressional districts to favor and/or disfavor competing political parties. The following example illustrates some of the fundamental ideas related to gerrymandering.

1.4. Links to the Informal Definitions in this Chapter

For your reference in the future, here are direct links to most of the bullet points in the list of foundational ideas discussed in this section.

Sets, including subsets, the empty set, unions of sets, and intersections of sets

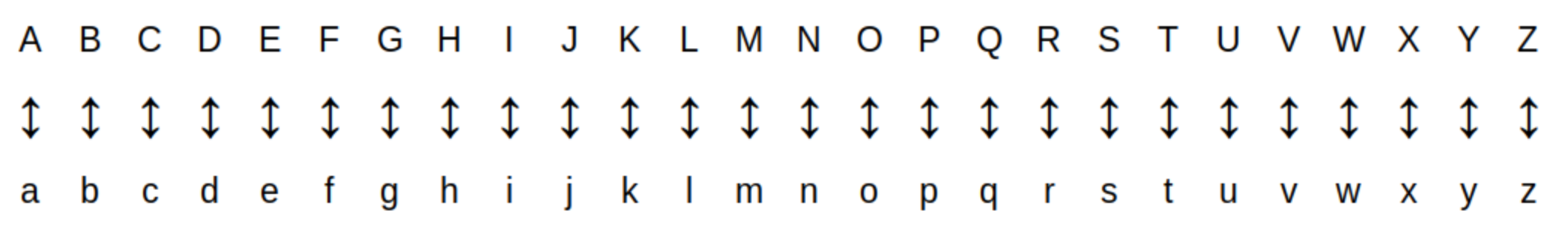

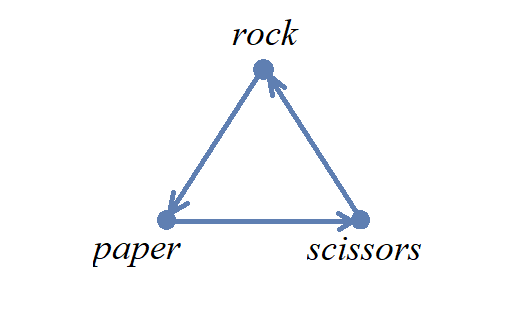

One-to-one correspondence, including the example "rock, paper, scissors"

Counting, including the Multiplication Principle and Pigeonhole Principle

Functions, including domain, codomain, range, inverse function, and the floor and ceiling functions \(\lfloor x \rfloor\) and \(\lceil x \rceil\)

Sequences, including index and terms

Recurrence Relations, including closed forms

Algorithms, including the Division Algorithm

2. Number Bases

NOTICE: If you are NOT enrolled in the CSC 230 course that I teach at SFSU, you probably are looking for the “public version” of the book, which I only update between semesters. The version you are looking at now is the “CSC230 version” of the book, which I will be updating throughout the semester.

This chapter was last updated on April 1, 2025.

It’s likely that you learned how to represent positive integers using the base-ten place-value system when you were young. This system uses ten symbols, the Hindu-Arabic numerals ‘0’, ‘1’, ‘2’, ‘3’, ‘4’, ‘5’, ‘6’, ‘7’, ‘8’, and ‘9’, to represent any natural number.

In the base-ten place-value system that uses decimal notation, each natural number is represented by a numeral which is a string of one or more of the ten Hindu-Arabic digits. However, in some computer science contexts, it is more useful to represent natural numbers in a place-value system that uses a different number base such as binary (base-two), octal (base-eight), or hexadecimal (base-sixteen). Using or thinking about numbers represented by numerals in these other systems can help you develop more efficient algorithms and recognize when certain numerals can be interpreted as encodings of multiple pieces of information.

In this chapter, you will learn how to represent natural numbers using place-value systems with bases other than ten.

Key terms and concepts covered in this chapter:

-

Number bases

-

binary

-

hexadecimal

-

octal

-

decimal

-

2.1. Numbers, Numerals, and Digits

In everyday life, it is common to treat numbers and numerals as if they are the same. However, it is important in this chapter to distinguish these concepts.

-

A number is an abstract idea or mental concept of a count, a measure, a rank in an ordering, etc..

-

A numeral is a word, phrase, symbol, or string of symbols that is used to represent a number.

-

A digit is a single symbol that represents a number. A digit is a numeral, but multiple digits can be combined to create other numerals. For example, each of the ten Hindu-Arabic numerals is a digit that represents a natural number that is less than ten, and multiple Hindu-Arabic numerals can be combined to create numerals that represent numbers that are greater than or equal to ten.

NOTE: The word "digit" comes from the Latin word digitus which means "finger" or "toe."

2.2. Review Of The Base-Ten Place Value System

It’s likely that everything you are about to read in this section is knowledge you’ve had for many years. The purpose of stating everything so explicitly is to provide an example you can compare with place-value systems that use other bases.

A base-ten numeral is a string formed from one or more digits (i.e., Hindu-Arabic numerals.)

-

The string is read from left-to-right.

-

Each digit in the string represents a multiple of a power of the base, ten, depending on the its position in the string.

-

The rightmost place represents a multiple of 1 (which is ten raised to the power zero) and each of the other places represents a multiple of a power of ten that is one greater than the power of ten represented by the place to its right.

-

Notice that the base itself, the number ten, is represented by the string "10" in this place-value system. The string "10" represents the number described by the phrase "1 ten plus 0 ones".

-

As an example, the string "101" represents the number described by the phrase "1 hundred plus 0 tens, plus 1 ones," where 1 hundred is the same as ten tens. That is, \[ 101 = 1 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 + 0 \cdot 10 + 1 \cdot 1 \] The expression on the right-hand side of the previous equation is referred to as expanded form in school-level mathematics.

NOTE: The Hindu-Arabic numerals evolved from earlier Brahmi versions. You can look at the image at this web page which shows a few steps in this evolution. Also, you can learn more about the history of the Hindu-Arabic numerals from the links in the "Notes" and "References" sections of this Wikipedia page.

2.2.1. An Algorithm That Computes The Digits Of A Base-Ten Numeral

In this subsection, an algorithm is presented for computing the digits in the expanded form of a base-ten numeral of the natural number \(n.\) This may seem to be a complicated way to do something very simple since we could just read off the digits, but the important thing to notice about this algorithm is that the role that ten plays can be played by any other positive integer constant greater than one! This means that this algorithm can be adapted to find the "digits" in the expanded form of a base-\(b\) numeral for the number \(n\) for any base \(b\) we choose.

-

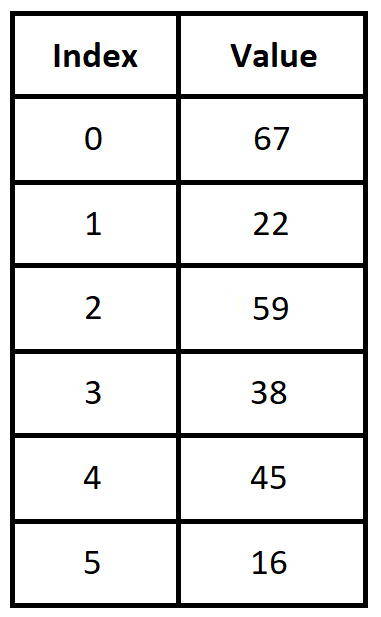

Task: Given the natural number n, compute an array of natural numbers \(s = [ r_{0}, \, r_{1}, \, \ldots \, r_{k} \)] so that each of \(r_{0}, r_{1}, \ldots , r_{k}\) is represented by a single digit in base-10, and \[ n = r_{k} \cdot 10^{k} + \ldots + r_{1} \cdot 10^{1} + r_{0} \cdot 10^{0} \] where \(k\) is the greatest natural number such that \(10^{k} < n.\)

-

Input: The natural number \(n\)

-

Steps:

-

Set \(a\) equal to \(n\)

-

Set \(s\) to the empty array (We will append the values \(r_{0}, r_{1}, \ldots , r_{k}\) to the array \(s\) as we compute them)

-

Divide \(a\) by 10 to find natural numbers \(q\) and \(r\) such that both \(a = q \cdot 10 + r\) and \(0 \leq r < 10.\)

-

Append \(r\) to the end of array \(s.\)

-

If \(q \neq 0\)

-

set \(a\) equal to \(q\)

-

go to step 3

-

-

Return the sequence \(s.\)

-

-

Output: An array of natural numbers \(s = [ r_{0}, \, r_{1}, \, \ldots \, r_{k} \)] where each number is represented by a single digit, and \[ n = r_{k} \cdot 10^{k} + \ldots + r_{1} \cdot 10^{1} + r_{0} \cdot 10^{0}.\]

-

That is, we rewrite \(n\) as \(r_{0} + 10 \cdot (r_{1} + 10 \cdot (r_{2} + \ldots r_{k-1} + (10 \cdot (r_{k})) \ldots ))\)

2.3. The Base-Two Place Value System (Binary Notation)

This subsection describes the base-two (binary) place value system. You will see that much of what is written here is the result of replacing "ten" by "two" in the description of the base-ten (decimal) system in the previous section.

A base-two numeral is a string formed from one or more of the two binary digits (or bits) ‘0’ and ‘1’.

-

The string is read from left-to-right.

-

Each digit in the string represents a multiple of a power of the base, two, depending on the its position in the string.

-

The rightmost place represents a multiple of 1 (which is two raised to the power zero) and each of the other places represents a multiple of a power of two that is one greater than the power of two represented by the place to its right.

-

Notice that the base itself, the number two, is represented by the string "10" in this place-value system. The string "10" represents the number described by the phrase "1 two plus 0 ones".

-

As an example, the string "101" represents the number described by the phrase "1 four plus 0 twos, plus 1 ones," where 1 four is the same as two twos. That is, \[ 101 = 1 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 + 0 \cdot 10 + 1 \cdot 1 \text{ (🤯: Wait… WHAT?!?) }\] Yes, this equation, which may appear to be written in the base-ten system, is correct in the base-two place value system, too! "10" is how the number two is represented in base-two notation!

As an analogy, the string "pie" signifies different things in English (a baked dessert) and Spanish (a foot.) You must take care to know which context you are working in!

|

It is traditional to use some extra notation to indicate when the strings "10" and "101" are not base-ten numerals to avoid confusion. In this textbook, numerals in any base other than ten will be written between a pair of parentheses followed by a subscript indicating the base. The subscript is written as a base-ten numeral. For example, we could rewrite the previous equation as \[(101)_{2} = (1)_2 \cdot (10)_2 \cdot (10)_2 + (0)_2 \cdot (10)_2 + (1)_2 \cdot (1)_2 \] which translates into base-ten as \(5 = 1 \cdot 2 \cdot 2 + 0 \cdot 2 + 1 \cdot 1.\) We can also write \(5 = (101)_2\) which is a way of saying that the base-ten numeral and the base-two numeral signify the same number. + NOTE: The reason we use base-ten numerals as the subscripts on numerals in other bases is because base-ten is so dominant: It is the "privileged" base, so we need to indicate when a different base is being used… and we don’t need to use the parentheses or subscripts if we are already working in base-ten. |

|

The parentheses and subscript are not necessary if it is clear from the context that a numeral is not a base-ten numeral. For example, \[ \text{chmod 755 hello.txt} \]

is a Unix/Linux command that changes the file permission bits (read, write, execute) of the file "hello.txt" for the file’s owner, the file’s group, and any other user. In this example, the string "755" is not a base-10 numeral, but is in octal (base-eight). Octal will be discussed later in the chapter. No subscript is used in the Unix/Linux command because it is natural to an experienced user of that operating system to use octal in the context. Also, we can omit the parentheses and subscripts if we want to tell a couple of "jokes:" |

You are ready now to learn how to represent numbers using base-two numerals.

2.3.1. An Algorithm That Computes The Digits Of A Base-Two Numeral

In this subsection, an algorithm is presented for computing the digits in the expanded form of a base-two numeral of the natural number \(n.\) This algorithm has been adapted from the one stated for base-ten in the previous section. Notice that all numerals used in this algorithm are base-ten numerals unless otherwise indicated.

-

Task: Given the natural number n, compute an array of natural numbers \(s = [ r_{0}, \, r_{1}, \, \ldots \, r_{k} \)] so that each of \(r_{0}, r_{1}, \ldots , r_{k}\) is represented by a single digit in base-2, and \[ n = r_{k} \cdot 2^{k} + \ldots + r_{1} \cdot 2^{1} + r_{0} \cdot 2^{0} \] where \(k\) is the greatest natural number such that \(2^{k} < n.\)

-

Input: The natural number \(n\)

-

Steps:

-

Set \(a\) equal to \(n\)

-

Set \(s\) to the empty array (We will append the values \(r_{0}, r_{1}, \ldots , r_{k}\) to the array \(s\) as we compute them)

-

Divide \(a\) by 2 to find natural numbers \(q\) and \(r\) such that both \(a = q \cdot 2 + r\) and \(0 \leq r < 2.\)

-

Append \(r\) to the end of array \(s.\)

-

If \(q \neq 0\)

-

set \(a\) equal to \(q\)

-

go to step 3

-

-

Return the sequence \(s.\)

-

-

Output: An array of natural numbers \(s = [ r_{0}, \, r_{1}, \, \ldots \, r_{k} \)] where each number is represented by a single digit, and \[ n = r_{k} \cdot 2^{k} + \ldots + r_{1} \cdot 2^{1} + r_{0} \cdot 2^{0}.\]

-

That is, the algorithm rewrites \(n\) as \(r_{0} + 2 \cdot (r_{1} + 2 \cdot (r_{2} + \ldots r_{k-1} + (2 \cdot (r_{k})) \ldots ))\)

Here is a link to an alternate method of finding the base-two numeral for a number.

If you made it to this sentence without skipping any of the discussion above, congratulations! If you did skip some of the discussion, go back and try your best to understand what the algorithm in the previous example is computing: The array \(s\) holds the digits, in reverse order of the binary notation for the number \(n.\) Compare what is done in this algorithm to the one for base-ten in the previous section… they are computing the digits for a numeral, but in different bases. If you can understand this algorithm, you will likely understand the rest of the chapter.

2.4. The Base-\(b\) Place Value System

If you made it here, you are ready to learn how to find, given any natural number \(n,\) the numeral that represents \(n\) in the base-\(b\) place value system (It is assumed that the base \(b\) is a natural number greater than or equal to 2.) You can compare the algorithm and example in this subsection to the ones in the preceding subsections for base-ten and base-two.

A base-\(b\) numeral is a string formed from one or more digits out of a set that contains \(b\) symbols, where each symbol is called a "base-\(b\) digit."

-

The string is read from left-to-right.

-

Each digit in the string represents a multiple of a power of the base, \(b,\) depending on the its position in the string.

-

The rightmost place represents a multiple of 1 (which is \(b\) raised to the power zero) and each of the other places represents a multiple of a power of \(b\) that is one greater than the power of \(b\) represented by the place to its right.

-

Notice that the base itself, the number \(b,\) is represented by the string "10" in the base-\(b\) place value system. The string "10" represents the number described by the phrase "1 \(b\) plus 0 ones".

-

As an example, the string "101" represents the number described by the phrase "1 b-_squared plus 0 _b, plus 1 ones." That is, \[ 101 = 1 \cdot 10 \cdot 10 + 0 \cdot 10 + 1 \cdot 1 \text{ (🤯: Again?!?) }\] Yes, this equation is correct, too, in the base-b place value system!

To avoid confusion, you can enclose each numeral in a pair of parentheses followed by the subscript \(b\) to indicate the base, where \(b\) is written as a base-ten numeral. For example, the previous equation can be written as \[(101)_{b} = (1)_b \cdot (10)_b \cdot (10)_b + (0)_b \cdot (10)_b + (1)_b \cdot (1)_b \] which translates into base-ten as \(b^2 + 1 = 1 \cdot b \cdot b + 0 \cdot b + 1 \cdot 1.\)

2.4.1. An Algorithm That Computes The Digits Of A Base-\(b\) Numeral

This is an adaptation of the algorithm presented earlier for base-two. Notice that all numerals used in this algorithm are base-ten numerals unless otherwise indicated.

-

Task: Given the natural number n, and positive integer constant \(b > 1\) compute an array of natural numbers \(s = [ r_{0}, \, r_{1}, \, \ldots \, r_{k} \)] so that each of \(r_{0}, r_{1}, \ldots , r_{k}\) can be represented by a single digit in base-\(b\), and \[ n = r_{k} \cdot b^{k} + \ldots + r_{1} \cdot b^{1} + r_{0} \cdot b^{0} \] where \(k\) is the greatest natural number such that \(b^{k} < n.\)

-

Input: The natural number \(n\)

-

Steps:

-

Set \(a\) equal to \(n\)

-

Set \(s\) to the empty array (We will append the values \(r_{0}, r_{1}, \ldots , r_{k}\) to the array \(s\) as we compute them)

-

Divide \(a\) by \(b\) to find natural numbers \(q\) and \(r\) such that both \(a = q \cdot b + r\) and \(0 \leq r < b.\)

-

Append \(r\) to the end of array \(s.\)

-

If \(q \neq 0\)

-

set \(a\) equal to \(q\)

-

go to step 3

-

-

Return the sequence \(s.\)

-

-

Output: An array of natural numbers \(s = [ r_{0}, \, r_{1}, \, \ldots \, r_{k} \)] where each number is represented by a single digit in base-\(b,\) and \[ n = r_{k} \cdot b^{k} + \ldots + r_{1} \cdot b^{1} + r_{0} \cdot b^{0}.\]

-

The algorithm rewrites \(n\) as \(r_{0} + b \cdot (r_{1} + b \cdot (r_{2} + \ldots r_{k-1} + (b \cdot (r_{k})) \ldots )).\) The result \(s\) contains the numbers that let you write \(n\) in base-\(b\) notation.

2.4.2. Octal Notation (Base-8)

2.4.3. Hexadecimal Notation (Base-16)

2.4.4. A Theorem (To Be Proven Later)

We can summarize what the algorithm does as a mathematical theorem, though technically at this point, it’s only a conjecture, an educated guess based on a few cases that seem to indicate that the algorithm will always work. You will learn a technique that will prove the theorem by validating the algorithm for all choices of natural numbers \(n\) and \(b>1\) in the Proofs: Mathematical Induction chapter.

2.5. Converting From Base-\(b\) to Base-Ten

In this section you will learn how to rewrite a base-\(b\) numeral in base-ten.

Several common bases used in computer science are base \(2\), base \(8\), and base \(16\), which are referred to as binary, octal, and hexadecimal, respectively. Binary digits are often referred to as bits. Note that, when finding the hexadecimal expansion of a positive integer, in addition to the usual digits \(0\) through \(9,\) we require an additional 6 digits. We will represent these by the letters \(\mathrm{A}\) through \(\mathrm{F}\), where \((\mathrm{A})_{16} = 10,\) \((\mathrm{B})_{16} = 11,\) \((\mathrm{C})_{16} = 12,\) \((\mathrm{D})_{16} = 13,\) \((\mathrm{E})_{16} = 14,\) and \((\mathrm{F})_{16} = 15.\)

2.6. Base Conversion Among Binary, Octal, and Hexadecimal

One of the ways that octal (base-eight) and hexadecimal (base-sixteen) are used in computer science is to abbreviate long bitstrings. The following examples will show how this is done.

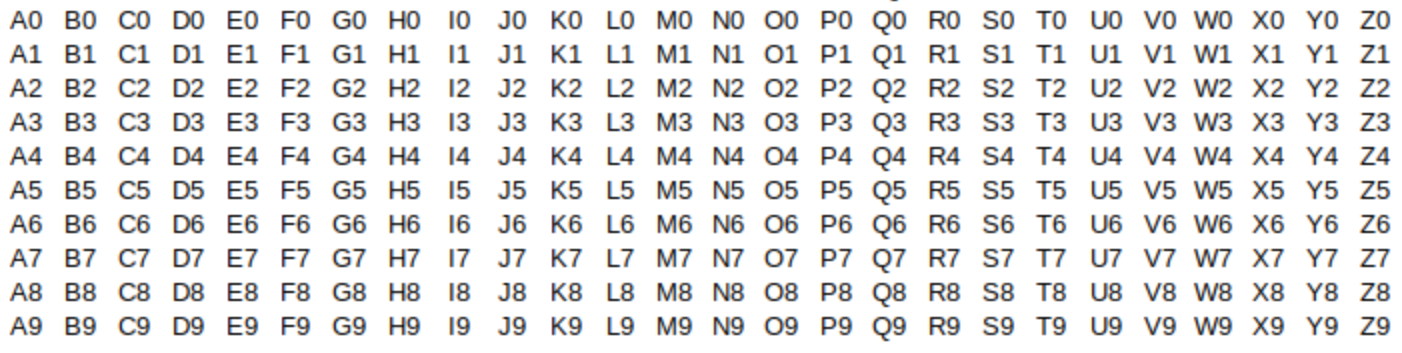

Suppose you need to convert a numeral from hexadecimal to binary. One method would be to first convert from hexadecimal to decimal, and then convert the result from decimal to binary. However, it is much more efficient to notice that since \(2^4 = 16,\) you can express each hexadecimal digit as a block of 4 bits (that is, a bitstring of length 4) as follows:

You can then concatenate the blocks, and remove any leading zeros if you need to.

To convert a numeral from binary to hexadecimal, first break up the binary notation into blocks of 4 bits, adding a suitable number of leading zeros if necessary. Next, convert each block of 4 bits to a hexadecimal digit and concatenate the results, removing any leading zeros if necessary.

A similar method can be used to convert between octal and binary. Since \(2^3 = 8,\) each octal digit can be written uniquely as a block of 3 bits as follows:

We then concatenate blocks, removing any leading zeros if necessary.

Also, the following table can be used to covert quickly between decimal, hexadecimal, octal, and binary in a similar way.

Conversion table for different bases

Decimal |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

Hexadecimal |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

A |

B |

C |

D |

E |

F |

Octal |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

Binary |

0 |

1 |

10 |

11 |

100 |

101 |

110 |

111 |

1000 |

1001 |

1010 |

1011 |

1100 |

1101 |

1110 |

1111 |

2.7. Exercises

-

Convert to decimal (base 10)

-

\((10262)_7\)

-

\((30A8)_{16}\)

-

\((1000010001100)_2\)

-

\(({12307)}_{60}\)

-

-

Convert \(\left(2039\right)_{10}\) from decimal (base 10) to

-

base 7

-

binary

-

hexadecimal (base 16)

-

octal (base 8)

-

-

Convert \(\left(2599\right)_{10}\) from decimal to

-

base 5

-

binary

-

hexadecimal

-

base 3

-

-

Convert the following hexadecimal numerals to binary numerals

-

\(\left(6F203\right)_{16}\)

-

\(\left(3FA20C45\right)_{16}\)

-

\(\left(FACE\right)_{16}\)

-

-

Convert the following binary numerals to hexadecimal numerals

-

\(\left(1111100111010101101\right)_2\)

-

\(\left(\ 10001111101011\right)_2\)

-

\(\left(1100101011111110\right)_2\)

-

3. Counting: Arithmetic Techniques

NOTICE: If you are NOT enrolled in the CSC 230 course that I teach at SFSU, you probably are looking for the “public version” of the book, which I only update between semesters. The version you are looking at now is the “CSC230 version” of the book, which I will be updating throughout the semester.

This chapter was last updated on February 2, 2025.

Contents locked until 11:59 p.m. Pacific Standard Time on May 23, 2025.

You probably learned how to count objects one by one when you were a child. You may have counted up to 5 on the fingers on one hand, or up to 10 on the fingers of two hands, or up to 20 on fingers and toes - that is, you paired the objects (fingers and/or toes) with number names to create a one-to-one correspondence. You may have counted all the way up to 100.

However, many problems in computer science or mathematics require you to count the number of elements in sets that contain millions of elements, or billions of elements, or even more elements, so counting one by one is inefficient or impossible. Starting with this chapter, and continuing later in the Set Theory and Counting: Permutations and Combinations chapters, you will study ways to quickly and efficiently count the number of elements of any set no matter the size of the set.

Key terms and concepts covered in this chapter:

-

Counting arguments

-

Sum Rule

-

Product Rule

-

Division Rule (also called the Rule Of Quotient)

-

Subtraction Rule (also called the Principle of Inclusion-Exclusion for two sets)

-

-

The pigeonhole principle

3.1. Some Foundational Counting Principles

Each of the four arithmetic operations corresponds to a rule we can use to count quickly.

3.1.1. The Sum Rule

The sum rule, also called the addition principle or the rule of sum, describes the number of possible choices of one element from a union of two sets that share no common elements (Such sets are called disjoint sets).

This is called the sum rule for counting because it involves adding to find a total. The sum rule can also be extended to more than two sets, as long as every pair of the sets have no elements in common.

3.1.2. The Subtraction Rule

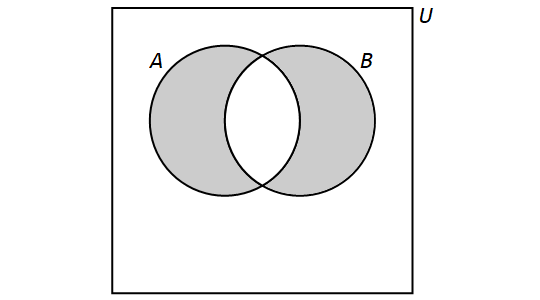

The subtraction rule describes the number of possible choices of one element from a union of two sets that do share one or more common elements.

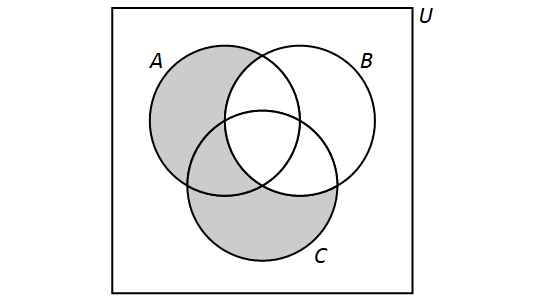

The subtraction rule is a special case of the inclusion-exclusion principle that involves only two sets. The inclusion-exclusion principle is discussed in more detail in the Set Theory and Proofs: Mathematical Induction chapters.

Video Example

The following video example features Dr. Joshua Roberts, Associate Professor of Mathematics at Georgia Gwinnett College.

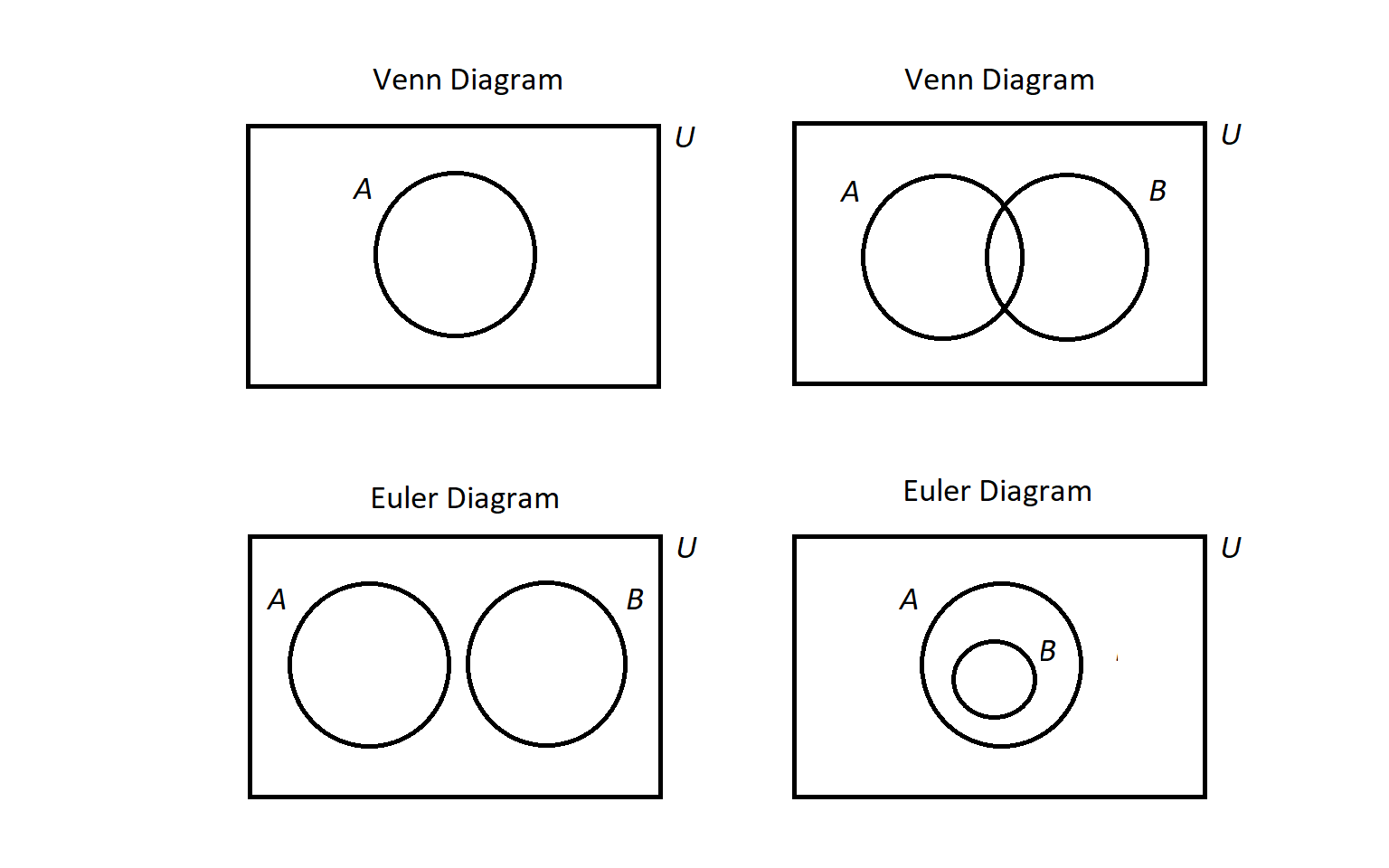

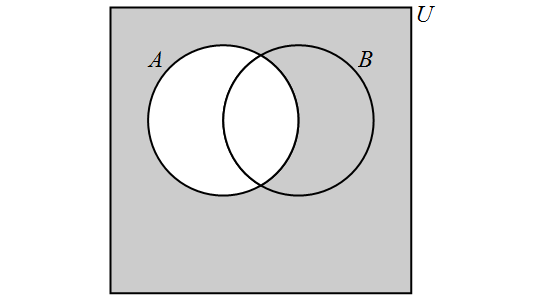

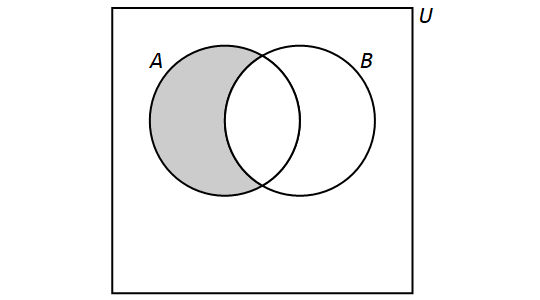

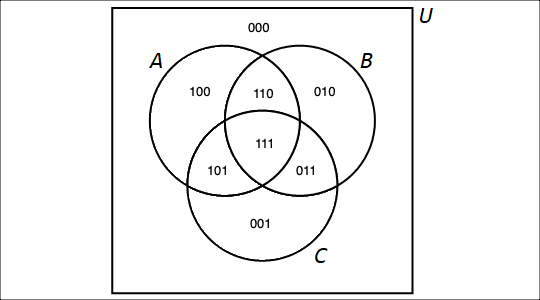

Notice that Dr. Roberts uses a Venn diagram to represent the sets in this video. Venn diagrams are covered in the Set Theory chapter of the Remix.

3.1.3. The Product Rule

The product rule, also called the multiplication principle or the rule of product, describes the number of possible choices of two successive elements where the first element comes from one set and the second from another set (which could be the same set as the first set).

To find the total number of outcomes for two or more successive events where both events must occur, multiply the number of outcomes for each event together. For instance, if you want to find the number of outcomes possible when you roll a die and toss a coin, you could use the product rule. It is important to note that the events must be independent, meaning one doesn’t effect the other.

Video Example

The following video example features Dr. Joshua Roberts, Associate Professor of Mathematics at Georgia Gwinnett College.

3.1.4. The Division Rule

This rule is used when there are \(n\) ways to complete a procedure, but each of those ways is equivalent to \(d\) ways (including the way itself.) That is, every possible outcome of the procedure can be done in \(d\) different ways

The next example uses both the product and division rules.

3.2. The Pigeonhole Principle

A suprising number of counting problems can be solved with the so-called pigeonhole principle.

Click here to see a photoshopped image that illustrates this principle.

3.3. Exercises

-

There are 67 mathematics majors and 124 computer science majors at a college. There is no student who is both a mathematics major and a computer science major.

-

In how many ways can two representatives be picked so that one is a mathematics major and one is a computer science major?

-

In how many ways can one representative be picked who is either a mathematics major or a computer science major?

-

-

A multiple-choice test contains 20 questions, and each question has four choices.

-

In how many ways can a student answer all of the questions on the test if each question must be answered?

-

In how many ways can a student answer all of the questions if the student is allowed to not answer one or more questions?

-

-

How many different three-letter initials, using uppercase English letters, are there?

-

How many different three-letter initials, using uppercase English letters, end with "R"?

-

How many bit strings are there of length five?

-

How many bit strings are there of length five that begin and end with 1?

-

How many bit strings are there of length less than \(n\), where \(n\) is a positive integer, that start and end with 1?

-

How many license plates can be made using three digits followed by four uppercase English letters if:

-

Digits and letters can be repeated?

-

Digits and letters cannot be repeated?

-

-

Each student in a Discrete Mathematics class is a mathematics major, a computer science major, or a double major in both mathematics and computer science. If the class has 5 mathematics majors (including double majors), 23 computer science majors (including double majors), and 7 double majors, how many students are in the class?

-

Suppose a computer system requires a password of length no less than 7 and no more than 10 characters, and each character must be an English lowercase letter, an English uppercase letter, a digit, or one of six special characters (*, >, <, !, +, =).

-

How many different passwords are available?

-

Suppose a hacker can check a potential password once every nanosecond (1 nanosecond is \(1 \times 10^{-9}\) seconds). How long will it take the hacker to check every potential password?

-

-

Suppose that there are 29 students in a class, all of whose last names use only English letters. Explain why at least 2 students in the class have last names that begin with the same letter.

-

Show that in any set of 5 integers, there are at least two of them that have the same remainder when divided by 4.

-

A bag contains 8 red balls and 7 blue balls.

-

How many balls must be chosen to be sure of choosing 3 of the same color?

-

How many must be chosen to be sure of choosing 3 red balls?

-

-

Someone cleaning out their attic finds a box containing 12 rock CDs and 12 country CDs. What is the minimum number of CDs they can take out to guarantee at least one of each type?

-

Give an argument that there are at least two people in California with the same number of hairs on their head.

4. Set Theory

NOTICE: If you are NOT enrolled in the CSC 230 course that I teach at SFSU, you probably are looking for the “public version” of the book, which I only update between semesters. The version you are looking at now is the “CSC230 version” of the book, which I will be updating throughout the semester.

This chapter was last updated on September 15, 2025.

Fixed some typos.

Set theory, along with logic, is the foundation of mathematics in our time. In earlier eras, people tried to use arithmetic (e.g., counting and whole numbers) and geometry (e.g., measurement of lengths, areas, and volumes along with geometric constructions) as the foundations of all mathematics. However, over the last two centuries, mathematicians gained new understandings of issues with these traditional foundations which led them to seek a new, firmer foundation. For now, that firmer foundation uses set theory: The study of collections of objects and how those collections can be combined, associated, and themselves added to other collections.

NOTE: If you want to dig much more deeply into what the issues with using arithmetic or geometry as the foundation of mathematics are, you can start with this Wikipedia page which includes a a brief description of the "foundational crisis of mathematics."

Key terms and concepts covered in this chapter:

-

Sets

-

Subsets of a set

-

The empty set

-

The power set of a set

-

Cartesian products

-

-

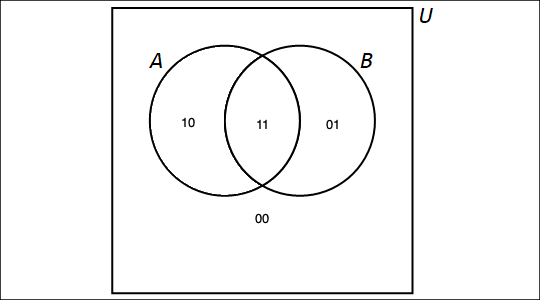

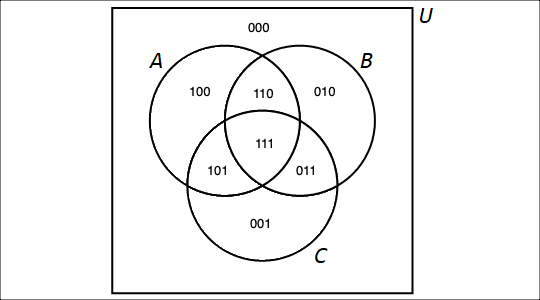

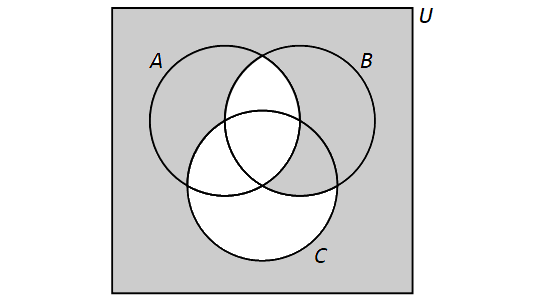

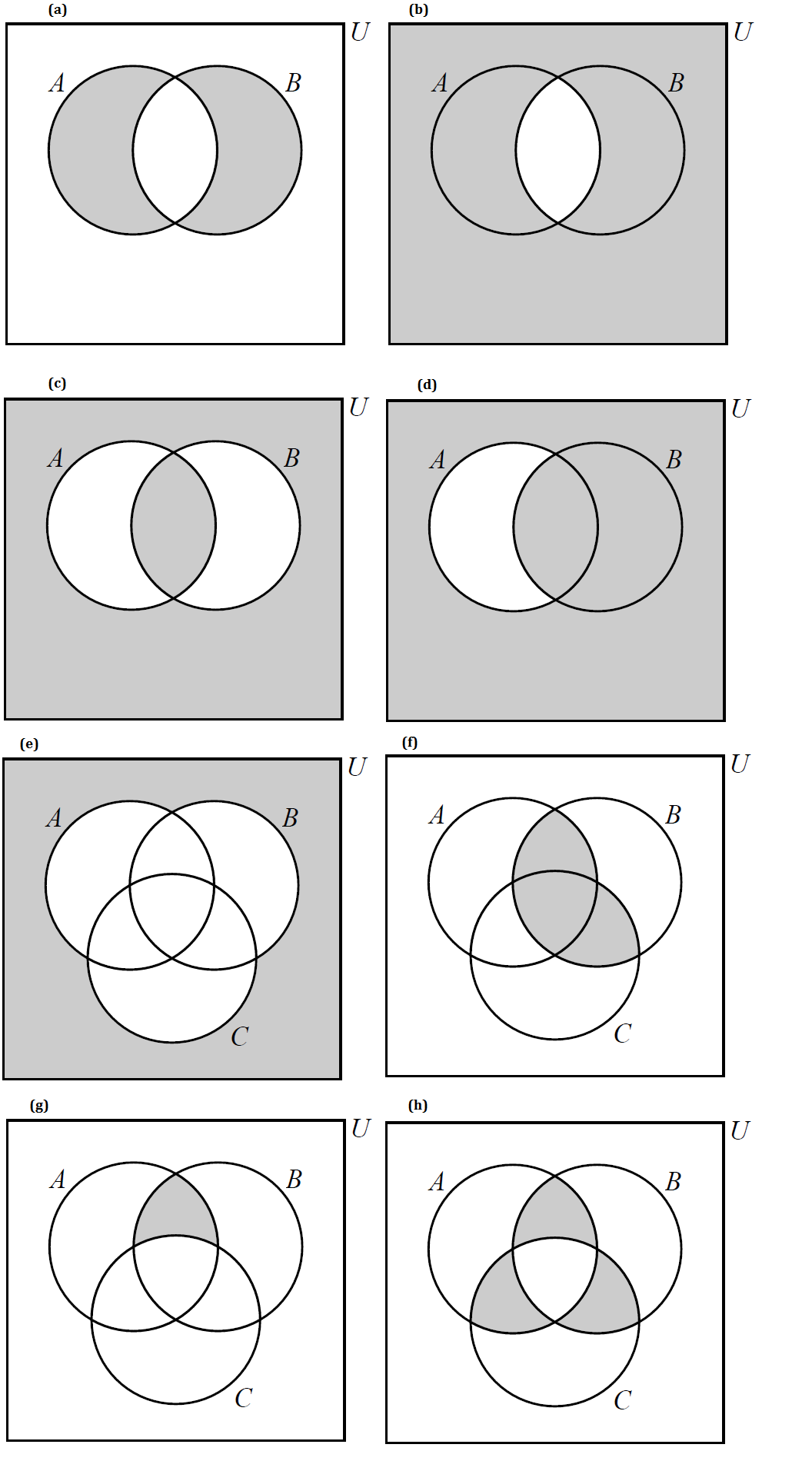

Venn diagrams

-

Cardinality and countability of finite and infinite sets

-

Set cardinality and counting

-

-

Operations with sets: Union, intersection, complement, and others

-

DeMorgan’s laws

-

Inclusion-exclusion principle

-

4.1. Sets

A set is an unordered collection of objects, called elements or members. A set is said to contain its elements.

If \(x\) is an element of the set \(S,\) then we write \(x \in S\). If \(x\) is not an element of the set \(S\), then we write \(x \not\in S\). For example, if \(S\) is the set of names of states in the United States of America, then “New York” is an element of \(S\) and “Ontario” is not an element of \(S,\) that is \[ \text{“New York”} \in S \text{ and } \text{“Ontario”} \not\in S. \] As another example, if \(E\) is the set of even integers, then \(2 \in E\) and \(3 \not\in E.\)

4.1.1. Describing A Set: The Roster Method